Apologies for formatting errors that I can’t seem to fix in this post.

Lloyd Alexander’s first novel for children is a tour guide of slightly cat-centric history and a promise of things to come. This bibliography is going to be fun.

Title: Time Cat

Title: Time Cat

Author: Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007)

Original Publication Date: 1963

Edition: Puffin Books (1996), 206 pages

Genre: Fantasy. Historical Fiction.

Ages: 7-10

First Line: Gareth was a black cat with orange eyes.

A somewhat immature boy named Jason is sulking in his room after a bad day when his cat Gareth decides to speak to him. Jason (whose last name is never given, but I expect it’s probably Little) accepts this easily enough – Jason had always been sure he could if he wanted to and it’s left at that. However, he is surprised when Gareth shares a feline secret with him: cats don’t have nine lives, but they can visit nine lives, and Gareth has only been waiting for an “important reason” to do so. Jason gets to come along on a trip from Ancient Egypt to the American Revolution, learning about cats, people and life along the way.

Time Cat is a fairly perfect independent read for kids who are ready to tackle books without any illustrations. It’s a good standalone tale with adventure, humour and a cool premise: when cats disappear from a room they have actually gone time traveling. Short segments sustain the action, an occasional slimy villain pops up to threaten Jason and the situations he lands in are different enough from one to the next that any child should be fully entertained. Incidentally being introduced to the writing of Lloyd Alexander is just a bonus for down the road. Of course, Time Cat‘s very excellence for young kids dooms it to a fairly short shelf life, as it is so broadly sketched as to be soon outgrown in favor of deeper fantasy and historical narratives. That’s as it should be and it is certainly worth all 100+ Magic Treehouse books, and will do far more good for a child’s vocabulary, imagination and shelf space. To give an example: in Italy, 1468, Jason meets a boy called Leonardo (hint, hint) who shows him his room – the sort most scientifically-minded boys have probably wanted at one time or another.

Inside, Jason looked with amazement–tables crowded with piles of paper; collections of butterflies, rocks, pressed flowers. A squirrel raced back and forth in a small cage. In another cage, a sleepy green snake lay coiled. Great bottles and jars held clumps of moss and long-tailed, speckled lizards. From another bottle, a few fish stared at the inquisitive Gareth.

On a table, Leonardo had set a water bottle over a candle flame. “Did you ever notice how the bubbles come up?” Leonardo asked. “I’ve been watching them. There must be something inside, something invisible–I don’t know what it is. Perhaps the philosophers in Florence know and some day I’ll ask them. First, I want to try to find out for myself.”

A quick rundown of places visited: The obvious cliche and weakest segment in ancient Egypt where cats are worshipped as gods; time spent tramping with the Roman legionaries before getting captured by some agreeable Britons; meeting a medieval Irish princess (with red-gold hair and a penchant for chatter, by the way) and a dignified slave by name of Sucat; teaching Japanese boy-Emperor Ichigo to stand up to his Regent, Uncle Fujiwara; meeting young Leonardo Da Vinci in Italy as he tries to convince his father that he’s an artist, not a notary; hanging out in post-Pizarro Peru; greeting the original Manx cat as she washes ashore on the Isle of Man; trying to avoid a nasty death in witch-burning Germany; and finally taking the rural tour of America in 1775.

Almost every segment is two chapters long and everywhere they go Gareth imparts some fortune cookie wisdom like “even a kitten knows if you wait long enough someone’s bound to open the door.” Jason isn’t very proactive on their journey – whatever age he is, it’s apparently too young for active military service. Instead, he observes people and learns about life from them, to return home a steadier and wiser boy. Fantasy novels have a natural aspect of initiation and this one is no different, as Gareth points out at the end that he took Jason with to help him grow. There’s even a (very mild) sacrifice come journey’s end before Jason returns home in a cross between the movie version of The Wizard of Oz and Where the Wild Things Are.

Time Cat was Lloyd Alexander’s first novel for children after a string of flops, including a translation of Sartre’s La Nausée, which got roasted (along with Nausea itself) by Vladimir Nabokov. The moral: aim high and at least the giants themselves shall smite you. Alexander finally changed gears as he neared forty, and later described writing Time Cat as “the most creative and liberating experience of my life.” There’s a real joy that comes through the book, as it’s so clear that Alexander was simply enjoying the freedom of his new path in life. He loved cats, so they feature prominently. His villains are an entertaining series of oily and absurd caricatures, with the German witch-judge a standout:

The eldest judge, a bony, black-robed man with a lantern jaw and eyes as sharp as thorns, shuffled through some parchment sheets on the table. “We have studied your cases thoroughly,” he began, licking his lips, as if tasting every word.

“You’ve had no time to study anything,” shouted the miller.

The judge paid no attention. His little eyes turned sharper than ever as he read from his parchments.

“The accused witch, Johannes the miller: guilty.”

“The accused witch, Ursulina: guilty.”

“The accused witch, Master Speckfresser: guilty.”

“One demon disguised as a boy disguised as a demon: guilty.”

“One demon disguised as a cat: guilty.”

The judge set down his papers. “You will be burned at the stake in the morning. Believe me,” he added with a smile, “this is all for your own good.”

Alexander’s writing is comfortable and witty, although it’s not quite polished enough to qualify as a great read-aloud on this early outing. He tosses around historic images like favorite toys, expecting kids to grasp the concept of centurions and Imperial Obeisance through context, rather than interrupting the plot to explain different factoids. Because of this it’s very light on educational material compared with more modern historical fiction for the same age group, and it has recently received some pointless criticism for cultural stereotyping. Honestly though, it’s for eight year olds. Try capturing a child’s imagination by explaining how the Incas were “exactly like you and me,” and see how much they remember about the subject in a month. We always begin with the broadest stereotypes, gaining detail and nuance as we grow up – so the Incas are memorable because they have llamas, while the Egyptians worship cats and ancient Britons wave spears around. Such details are memorable and interesting to a young child, and then swiftly outgrown as their reading naturally progresses.

Time Cat is simply a delightful experience at the right age. I read it avidly at around nine or so, and then within a couple of years I had moved on to Alexander’s far more mysterious Rope Trick. It’s easy to recommend and, while I don’t know exactly how consistent a writer Lloyd Alexander was over his long career, I’m looking forward to finding out.

The Parental Guide up next, with some spoilers as always.

Violence: Death hangs over Jason’s head multiple times, including three threats of getting burned alive, but he never sustains any injury and after the danger is brought up it’s always swiftly negated. There are no other casualties until the final segment, when the likable Professor Parker is hit by British fire, though it’s never clear if he dies, since this is all we get: He smiled and tried to pull a shilling out of Jason’s ear, but his hand went slack and the coin dropped to the earth.

It is mentioned that cats are regularly killed in 1600 Germany, but none of the animal characters in the book suffer any harm. If you’re wondering, the “sacrifice” I mentioned Jason makes upon returning home is that Gareth will no longer be able to speak to him, but they will still understand one another without words.

Values: Sucat in the Ireland segment has a secular role, but it is revealed in a rather solemn moment at the end that Jason has actually just met Saint Patrick.

Cats are life’s great treasure, and this is not the last time Alexander would write a supremely cat-centric fantasy. In fact, it ends up such a trademark of his that I’m fairly surprised he kicked off his Prydain Chronicles with the hunt for an oracular animal of the porcine persuasion.

Monarchy is a fairly suspect arrangement in Time Cat, with rulers in general portrayed as ridiculously isolated from their subjects.

During the quiet story on the Isle of Man, Gareth states that everyone is pretty if they have pride in themselves, demonstrated by Dulcinea the Manx cat who doesn’t envy Gareth his tail. He also states the theme of Alexander’s career heretofore: “Trying to make someone do what they aren’t really good at is foolish.”

The most eye-rolling bit is easily when Sayri Tupac the Great Inca lets Jason and Gareth (being held for ransom) go because Don Diego the Spaniard gives a mushy speech about peace and understanding between cultures. “Understanding is better than gold,” says Sayri Tupac. Well, it was the sixties…

Role Models: Jason is a completely bland character; while he improves on his journey, it’s mostly by observing other, more interesting people. Gareth is a better creation, wise and unflappable, and when it’s time to save the princess, it’s Gareth who battles and slays the threatening serpent.

Educational Properties: The historical sketches are very light on detail, so even though you could tie the characters of Ichigo and Uncle Fujiwara to their real counterparts, it really belongs in the entertainment and fluency pile.

End of Guide.

Alexander’s books appear with some frequency at my local used bookstore, and I will be acquiring them whenever I can. As always, I invite those who’ve read more of his work than I have to share their opinions.

Up Next: Going for a classic western, and an example of what young adults were probably reading in the 1940s.

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

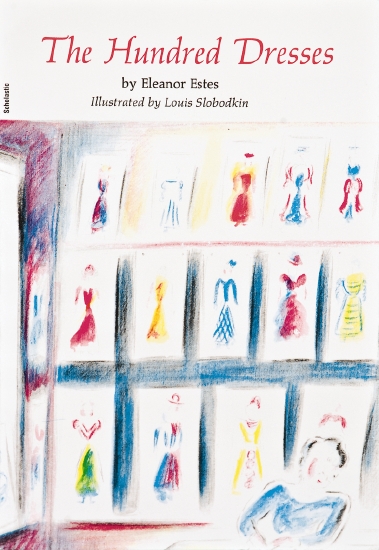

Title: The Hundred Dresses

Title: The Hundred Dresses

Title: Stuart Little

Title: Stuart Little