I was not originally planning to review very much young adult fantasy (or modern young adult in general) on the Castle, given how massively popular the speculative genres are right now, and given that a little over half of the readers of young adult books are adults themselves, who probably aren’t looking for a Parental Guide to Throne of Glass and the like. However, I have started to notice that almost all of the fantasy books being recommended to teens and getting discussed on YouTube are extremely modern, always post-Twilight, with the entirety of the post-Potter boom somehow forgotten about. This is strange, and a little disconcerting to be honest – I really thought writers of Patricia McKillip’s and Terry Pratchett’s caliber were sure to live on in YA memory. Guess not.

Meanwhile, the very conceit of this blog is that it’s for parents or planning-to-be-parents who want to construct a youth library at home, rather than trust modern libraries to do the job for them. As such, there’s no reason not to care about what’s in the books your eventual teenagers will be reading. So I will be reviewing books for teens in the same fashion as books for younger kids.

Thank you and on to the review…

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Author: Terri Farley (1950-)

Original Publication Date: 2005

Edition: Simon Pulse (2005), 279 pages

Genre: Fantasy. Romance.

Ages: 15-17

First Sentence: This is what it’s like to be crazy.

Everyone knows which novel swept the young adult world in 2005 (Twilight) and every young adult fantasy fan who cares about good writing, creative plots and believable characters knows that this book essentially ruined the genre, both by turning romance into a prerequisite (and people act like it’s a surprise boys don’t read) and incidentally creating the “Bella Swan backlash” that led to YA being flooded with sexually active assassin chick role models to compensate. Sadly, a far worthier alternative with a better take on paranormal romance was published that same year, a short standalone novel whose supernatural love interest was not a literal predator, whose heroine did not treat her humanity like last year’s shoes and whose author actually knew the meaning of the term “star-crossed.” While not a masterpiece, Seven Tears Into the Sea quietly offers some surprisingly good themes and a very pleasant atmosphere.

At ten years old, Gwen Cooke sleepwalked into the ocean and was rescued by a strange boy who vanished after whispering a mysterious poem in her ear:

Beckon the sea,

I’ll come to thee…

Shed seven tears,

Perchance seven years…

The incident became the focal point of small town gossip and her parents soon decided to move away and start fresh. Now, seven years later, Gwen returns to Mirage Beach to see her grandmother and find out the truth of her supposed hallucination. The truth turns up soon enough in the form of a cute guy named Jesse and Gwen has to fight rationality when all the evidence indicates that Jesse is a selkie.

It’s a little bit unusual to find the selkie legend transplanted to the Pacific but what could have been a disaster was rather cleverly utilized. Sea lions replace seals and the coast of northern California is suitably rocky and fog-bound, but what really makes it work is the clash of the old world and the new, ancient and modern ways of living. Gwen has the old country in her blood and in her red hair but like most modern people she’s been taught not to care. I wasn’t playing dress-up for the tourists, she thinks. Fantasy stories often have an initiation aspect, where the experience the main character has is impossible to share with the friends left behind and the same is true of this story, with tensions between Gwen and her city friends reaching a boil when the latter show up unexpectedly at the Summer Solstice celebrations.

Seven Tears is rather short on plot, compensating with leisurely charm. The second half of the book opens each chapter with an entry from a sea garden guide Gwen is creating, to wit:

Wild Western Thimbleberry

Wild Western Thimbleberry

(Rubus parviflorus)

Velvety pink berries, dark green leaves, and cautioning spines mark this woodsy berry. Cousin to the blackberry, it may live at the shore, in red-wood forests, and on the High Sierra, but deprived of moisture it will sicken and die. Thimbleberry wine is nectar to fairies, and herbal lore praises the thimbleberry for shielding the virtuous. Running through a thimbleberry thicket is rumored to dispel illness, while a sip of thimbleberry tea returns evil to those who wish it on others.

The Sea Horse Inn, run by Gwen’s grandmother Nana, hosts a proper tea. “Be certain you have your caddy spoons, mote spoons, serving plates, sugar tongs, cream pitcher…” Nana keeps a scrying glass in her pocket and tells folk tales to the guests. One of the locals plays the bagpipe. Gwen brings her cat to the cottage and protects the swallows’ nest above her porch door. The book is full of nice things, culminating again with Midsummer Eve, and because of this the pacing is unexpectedly languid. It’s as close as paranormal romance can get to regular slice-of-life, almost a seamless merger of genres. I expect this would frustrate a lot of fantasy fans, as there is no real magic to be found until the very end of the book. However, for readers more willing to put aside expectations, they’ll find the lifestyle Gwen is introduced to on Mirage Beach as lovely as a Pinterest board. I think that still counts as escapism.

Then everyone hushed at the bagpipes’ skirl.

Red wore a tartan kilt and a plaid fastened at his left shoulder. It was easy to overlook his knobby old-man knees and everyday orneriness while he played. He cradled the leather bag as if it were a child, and though I doubt anyone knew the song, they watched, faces turned amber by firelight, falling under a spell.

Jesse should really be at the center of this narrative but I find little to say about him because he’s rather thinly sketched. To begin with his attention is played for menace: His eyes darted past me, as if he’d block my escape. … He stood slowly, staying entirely too close. … He tossed out the words like a lure. He’s secretive about his life and he’s been seen with the wrong crowd but it’s all a red herring because this image of a dark, menacing lover from the ancient folktales turns out to be merely Gwen’s preconception. Being a selkie, Jesse is actually just a simple soul who likes to eat raw seafood and is bothered by enclosed spaces. And because Farley clearly loves animals he’s also a peaceful child of nature who wouldn’t hurt a living thing (although he’s a dab hand in a fistfight and, incidentally, a carnivore). This all makes for a neat subversion of the standard brooding hero with a dark past that crops up almost automatically in stories of this type but it ends up being less than satisfying because he doesn’t really have a past at all. It doesn’t help that the timeframe for this epic love story is one week. That was a hard sell even for Shakespeare.

Since Jesse is not dangerous and Gwen’s fear of inciting old gossip is revealed to be an empty worry, a villain is provided in the form of Zack McCracken, who looked like a young Brad Pitt who’d been living behind one of those dumpsters for a week and decided to crawl out for a joint. There is no love triangle here, nor hint of one. Zack belongs on a fishing boat but the fish are gone and as such he’s deteriorated into a full-time thug. As nice as the beachside appears, the scene isn’t fully set until Nana finally takes a reluctant Gwen to the local town of Siena Bay:

“Siena Bay has changed a lot, hasn’t it?” Nana asked, as if she’d noticed my head swinging around, taking it all in. “The Chamber of Commerce tries to keep the atmosphere of an old fishing village but-“

I followed Nana’s gesture and focused beyond the booths.

I remembered coming down to the docks at dawn with Mom. She’d buy me hot chocolate from Sal’s Fish and Chips, which was the only thing open that early. We’d watch sun-browned men shout and sling around nets before putting off into the turquoise water.

Now, though the nautical decorations remained, they draped a dozen places I could find in the Valencia mall.

“Someone must still fish,” I insisted.

“They try,” Nana allowed. “In fact, most of them still put out to sea every morning, but they have to supplement.”

Supplement? Was that a nice word for welfare? Or something shady? Nana had said the gang in town was made up of fishermen’s sons with nothing to do.

“They say it’s fished out and blame the sea lions and tourists,” Nana went on. “I blame it on pollution and the industrial fisheries, but not many listen to an old woman. I’m glad we’re up the coast a ways.”

With the setting so strongly emphasised throughout, the above passage must be seen as of key importance. The coastal way of life is dying, replaced by global tourism (guests at the inn are portrayed as a rather pointless bunch, with Tolkien enthusiasts and unhappily married couples) and this culture clash plays right into the Midsummer Eve celebration and the choices Gwen makes that directly impact the tragic ending, as Gwen sees the look on Jesse’s face. Anger wouldn’t have surprised me, or even sadness, but he looked as if I’d given up our very last night together.

Seven Tears Into the Sea is a good example of young adult fantasy, written right before the Twilight boom solidified all the cliches it’s now hard to avoid in paranormal romance. The novel also feels very personal. Terri Farley has otherwise kept to the topic of horses in all of her works, specializing in romantic “girl and her horse” series for pre-teen girls, both in the Phantom Stallion series (I read 15 of those books back in the day) and its spin-off Wild Horse Island. Seven Tears Into the Sea stands out as a unique entry in her catalogue and, given that it came out right alongside Twilight, it can’t claim to be influenced by that runaway success. In other words, Farley must have felt a strong compulsion to break form and write this story.

The writing is simple but fairly solid, with a well-rendered atmosphere and an effective example of present tense usage in the opening flashback, with the rest of the novel conveyed in the traditional past tense. This lends immediacy to Gwen’s memory of nearly drowning and keeps the rest of the novel from feeling like a wannabe movie script. The biggest flaws are the rushed ending and lack of developed subplots, but it’s a good choice for those readers who enjoy a cozy seaside atmosphere alongside their doomed romance. If you’re planning to read it yourself, you should stop here. Otherwise, spoilers below.

On the night of Midsummer’s Eve, there are bonfires to jump over, music and dancing, and games meant to single out the King and Queen of Summer. The locals takes pride in Gwen and Jesse’s accomplishment and there’s the sense of a growing bond not just between the two of them but also between them and the whole town. This is exactly what the ancient festivals were built to do: strengthen the bonds of family, friends, community and the new young couples that carry the future.

Then a voice sliced through the magic.

Gwen’s two city friends crash the festival, Mandi drunk and slutting around, Jill detached and critical of her surroundings, both demanding Gwen leave her Midsummer’s Eve coronation and return to the “real world” with them. Depressingly, her sense of obligation makes her do what they want – and Terri Farley portrays this as a horrible choice. At three thirty in the morning I was sprawled on my couch, eating pizza I didn’t want, with guests I didn’t welcome. Gwen washes the seawater from her hair and changes from her Midsummer dress into fresh jeans and a sweatshirt. Hungover Mandi tries to give her a bleach makeover and sarcastic Jill starts psychoanalyzing her new relationship. Her cat is victimized because the girls foolishly let Zack into the cottage in Gwen’s absence. Jesse then steps in to confront Zack – which leads to a mortal wound, sharks in the water, storms, magic and farewells. All this instead of watching the fires burn low and seeing the sun come up on Midsummer morn. For want of a nail… Gulls banked and cried, scolding me for not observing at least one Midsummer morn tradition. I was Queen, after all.

The resolution to the threat of Zack feels rushed and I believe Farley made a mistake by keeping Gwen away from the action, instead leaving readers with a fragmentary, secondhand account of violence on a boat and a shark attack. Without seeing any of it, this portion of the story lacks dramatic heft. Gwen heals Jesse via some mystical bond they have that was only briefly hinted at, finally acquiring proof that selkies are real just in time for the truth to hit her: Jesse can only return to the shore every seven years. Here we get what the story has been building to, and it’s a worthy payoff because Terri Farley won’t cheat her way to a happy ending. Gwen is stricken. “That would mean, after this summer, I’d be twenty-four before I saw you again. Then, thirty-one-” I kept counting on my fingers -“thirty-eight, forty-five, fifty-two! Jesse! Fifty-two. If we had kids, they’d be grown. I would have wrinkles around my eyes from staring out to sea, watching for you. I could die, and you wouldn’t hear of it for years.” This is the tragedy of Celtic legend updated for a modern setting. Gwen did give up her last night with him. There will be no Midsummer dancing next year, no crowning, no belonging – not with Jesse. This was a once in a lifetime experience that Gwen let herself be talked out of. That’s worth more than seven tears.

Parental Guide up next.

This is quite modest as modern teen romances go. There’s some passionate kissing and some underwater manhandling that would probably look sexy on film but isn’t graphic in print. It’s not aiming for the Printz longlist, in other words.

Violence: Zack gets eaten by a shark offscreen in what may be termed disproportionate retribution. Jesse’s fatal stabbing is described in the mildest possible terms – “blood” and “wound” are as graphic as the language gets. One fistfight which Gwen leaves in the middle of.

Values: Nature conservation is right up there among Terri Farley’s cardinal virtues. The loss of small-town economies, traditions and cohesion is also an obvious theme.

The book takes on a significant pagan holiday with great affection. Was this some Celtic deity’s way of convincing me he still ruled? Gwen wonders, which is as close as Farley gets to the religious aspect of all this.

Gwen’s parents vacate early on, leaving her to free-range for the summer in a cabin with no phone that’s just down the beach from her grandmother’s house. Convenient. Nana is the only parental figure around but she’s a very positive one.

Female friendship is not portrayed in a remotely positive light, as Gwen’s friends guilt-trip her hard for preferring Jesse to their drunken company. “You almost went off with him instead of us.” Jill retells Gwen’s childhood sleepwalking experience to Mandi (after Gwen told her in confidence) and the two of them also invite Zack into Gwen’s cabin, where he steals her cat – luckily he does return the cat alive. While in Gwen’s last scene with Mandi and Jill she thinks they’ll patch things up and continue on, that’s before she loses Jesse. It can only be hoped she finds some better friends after that.

Role Models: Gwen is a typical YA heroine – not too smart, not too quirky, somewhat insecure, easy to project on to – but she’s responsible, hard working and unselfish (to a fault, in fact), making for a decent heroine. Gwen later gives up her own happiness for Jesse’s when she refuses to steal his skin, knowing he would grow to hate her in time. This could be seen as a feminist commentary on the men in the old selkie legends who put any such scruples aside to keep their wives. On the other hand, it might also be seen as a girl putting her boyfriend’s needs before her own. No matter, as it’s quite poetic.

Jesse is masculine but non-threatening and socially rather awkward. He’s not an interesting character unless you’re a teenage girl, but (aside from the selkie problem) he’s not a walking warning label, which is a nice change.

Zack is clearly meant to be disliked (he’s both lewd and cruel to animals), while Mandi is incredibly annoying and infantile – not people to emulate or make excuses for.

Educational Properties: Unlikely, unless it inspires a teen to research the selkie legends.

End of Guide.

Terri Farley has not revisited the fantasy genre, and I’m left slightly non-plussed by the remainder of her bibliography. With twenty-four books in the Phantom Stallion series, it’s unlikely I’ll ever acquire the complete set, and my first thought was to simply discontinue her bibliography from time constraints. However, since I am planning to do the twenty Black Stallion books for this project (eventually), and since I remember Phantom Stallion as being higher than average quality compared with some of the other horse series I was reading as a child, I would like to do an overview of the series some day. Certainly all “easy read” franchises are not created equal, and the best ones deserve acknowledgement.

Up Next: Returning to Prince Edward Island for the continuing story of Anne Shirley…

Title: Black Duck

Title: Black Duck

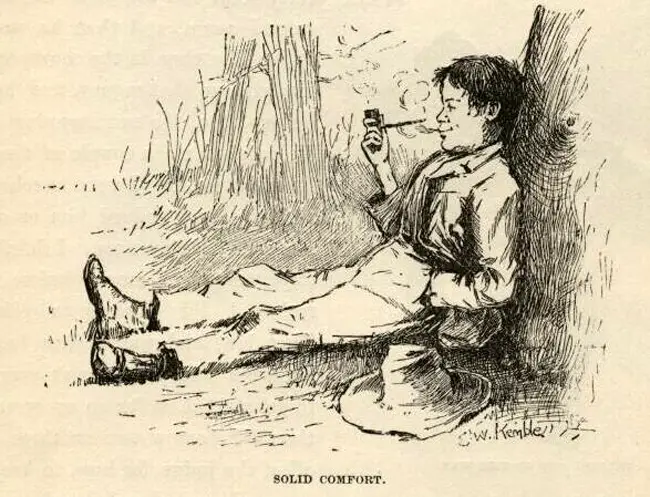

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Shane

Title: Shane