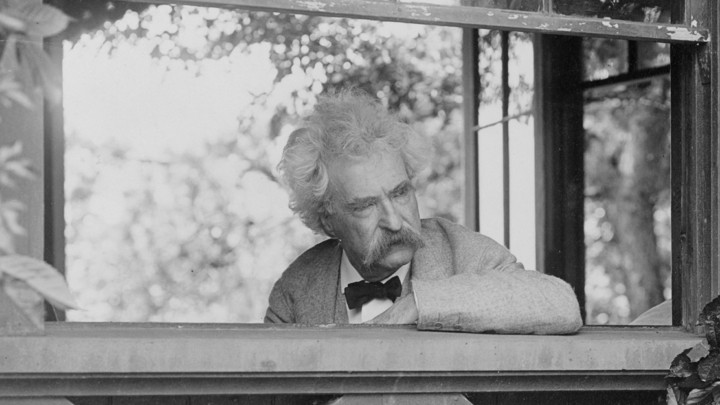

Mark Twain had many talents but Stratemeyer Syndication wasn’t one of them.

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

Author: Mark Twain (1835-1910)

Original Publication Date: 1896

Edition: The Complete Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Borders Classics (2006), 281 to 337 (56) of 337 pages.

Genre: Adventure. Mystery.

Ages: 11-13

First Sentence: Well, it was the next spring after me and Tom Sawyer set our old nigger Jim free the time he was chained up for a runaway slave down there on Tom’s Uncle Silas’s farm in Arkansaw.

Our scene opens upon a fairly decent description of spring fever on the parts of Tom and Huck, which leads immediately to an odd little passage as Huck details what thoughts this pent-up energy can lead to: …you want to go and be a wanderer; you want to go wandering far away to strange countries where everything is mysterious and wonderful and romantic. And if you can’t do that, you’ll put up with considerable less; you’ll go anywhere you can go, just so as to get away, and be thankful of the chance, too. This appears to be Twain’s way of saying the previous installment’s Arabian fantasia never happened, as the text otherwise refuses any acknowledgement of Tom Sawyer Abroad. Goodbye airship captain, hello Perry Mason.

Also, goodbye Jim, who is nowhere to be found in this volume. It’s certainly more realistic than having him continue to be part of the gang, but a big part of the allure to sequels is in the audience’s desire to find out what happened to previous characters. Would it have killed Twain to insert one line of explanation? Jim headed north. Jim joined the Underground Railroad. Jim hopped a ship on route to Liberia. Something.

This leaves Tom and Huck, bored and looking for adventure, when Tom’s Aunt Sally sends for them because Uncle Silas has been in an altercation with his neighbours, brothers Brace and Jubiter Dunlap. It’s not clear why Aunt Sally thinks that Tom and Huck will be an asset, a “comfort” in these hard times, considering their last visit included heavy gaslighting of both her and her husband, vandalism of house and property, inciting a mob to violence and getting Tom shot in the leg, but no matter. The boys head down on the riverboat and run into Jubiter’s identical twin, Jake Dunlap, who was presumed dead years ago and is now on the way home with a fortune in stolen diamonds and two angry ex-partners in hot pursuit. Everyone arrives in Arkansas and murder is the result. Tom Sawyer must take to the stand and defend his uncle to unveil the real murderer among them.

Since this is a mystery, I will do my best to avoid spoilers, just in case someone does intend to read this book.

As much trouble as I’ve had with the Tom Sawyer sequels thus far, there have always been praiseworthy elements, even in the dubious science fiction of Tom Sawyer Abroad. At that point it still felt like Mark Twain was enjoying some part of the money-grubbing process, as the book had glimmers of wit and elegant passages hidden away where you least expected them. However, in this final installment, all those better qualities have shrunk almost to nothing in a tale that seems to exist only for the entertainment of its closing chapter. Twain seems completely bored with proceedings, keeping Tom and Huck on a very tight leash until near the end, when Tom decides to borrow a neighbour’s bloodhound. Until that point they are simply observers of the action, unable to get into mischief because mischief would create subplots and this book was written to be published in a hurry – it’s the shortest in the series, 56 pages to Abroad‘s 80, and it feels it. In previous volumes, Tom and Huck’s intelligence levels have been on a dizzying see-saw, but this is the first time they’ve felt so tired as characters.

Tom Sawyer, Detective is a mystery, which is not a genre Twain was suited for. Incidentally, he was later accused of plagiarizing this plot from a Danish crime novella called The Vicar of Weilby (now more commonly translated as The Rector of Veilbye), written in 1829 by Steen Blicher and itself based on a true event from 1626. The two stories are admittedly quite similar, although the original Danish is way more depressing (big surprise). It doesn’t appear that a consensus has ever been reached on whether the allegation was true or not, and I couldn’t find any information outside of Wikipedia, so it does not appear to be a big source of debate at present. Let’s move on.

For the plot, Twain makes use of identical twins, a conceit he also engaged with in Pudd’nhead Wilson – the problem with bringing such a topic into a mystery setting is that readers know immediately that there will be a case of mistaken identity at some point. Meanwhile, Uncle Silas’s farm is clearly at the center of a mystical convergence, as once again a bunch of criminals all descend on the same stand of trees at the same time as Huck and Tom – it’s given a slightly more probable setup than it was in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but it certainly doesn’t make the already contrived plot feel any better. Then there’s the courtroom bit where Tom reveals the identity of an imposter because of a hand gesture he’d seen the man use before, and which the audience was never privy to in the first place. So the tale is at once predictable in its twists and impossible to “solve” alongside our erstwhile Perry Mason. All this on top of the problem that comes with Tom and Huck spending so much time watching and listening to other people rather than investigating. They spend four chapters thinking that their best clue is actually a supernatural occurrence, bogging the mystery down for the sake of a tired joke.

There are a couple of rays of light in all of this. First there’s the adorable scene where the boys wander across the countryside with a happy bloodhound, corpse-hunting. It’s a cute mix of ghoulish proclivities with classic childhood revels, and features the boys being proactive even though they feel like idiots for trying:

It was a lovely dog. There ain’t any dog that’s got a lovelier disposition than a bloodhound, and this one knowed us and liked us. He capered and raced around ever so friendly, and powerful glad to be free and have a holiday; but Tom was so cut up he couldn’t take any intrust in him, and said he wished he’d stopped and thought a minute before he ever started on such a fool errand. He said old Jeff Hooker would tell everybody, and we’d never hear the last of it.

So we loafed along home down the back lanes, feeling pretty glum and not talking. When we was passing the far corner of our tobacker field we heard the dog set up a long howl in there, and we went to the place and he was scratching the ground with all his might, and every now and then canting up his head sideways and fetching another howl.

It was a long square, the shape of a grave; the rain had made it sink down and show the shape. The minute we come and stood there we looked at one another and never said a word. When the dog had dug down only a few inches he grabbed something and pulled it up, and it was an arm and a sleeve. Tom kind of gasped out, and says–

“Come away, Huck–it’s found.”

This is an effective little scene hidden away in the midst of the slow plot, and the other entertaining portion is saved for the final courtroom scene, in which Tom takes to the stand to reveal the dastardly truth about every crime, stringing out each revelation for “effect” and feeling more like himself again – a final farewell to the brash, theatrical know-it-all. Energized by the limelight, Tom solves the case and gets the reward money, with our last glimpse of the pair summing up their friendship and their finest qualities in a rather beautiful sendoff: And so the whole family was as happy as birds, and nobody could be gratefuler and lovinger than what they was to Tom Sawyer; and the same to me, though I hadn’t done nothing. And when the two thousand dollars come, Tom give half of it to me, and never told anybody so, which didn’t surprise me, because I knowed him.

It’s a worthy goodbye to humble Huck and his compatriot, and I felt appropriately wistful as I closed the omnibus – an impressive feat, considering what a slog I found this volume to be. Despite building on established characters and settings here, I actually much preferred the wild departure of Tom Sawyer Abroad, which had greater amounts of wit, imagery and bafflement, wrapped in a sci-fi expedition that gave it a vague sense of fun. Tom Sawyer, Detective just made me wonder if Mark Twain were depressed when he wrote it. While very young kids might find the plot more surprising than their parents, I can’t recommend it when such series as Nancy Drew are so easily available.

To summarize my opinions on this series, there is sadly a good reason the last two volumes are so forgotten. They have not been unjustly spurned as I at first suspected, and even Twain’s use of the vernacular is far more sloppy than anything found in the truly perfectionist narrative he first gave Huck. When it comes down to it I would only recommend The Adventures of Tom Sawyer – a truly inspired and essential classic of children’s literature. Follow up with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn only if you’re studying the history of American literature, and the final two only from morbid curiosity. Reading all three sequels has not diminished the original though. Quite the opposite.

See Also: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer Abroad.

Parental Guide, with no spoilers.

Violence: It’s a murder mystery for kids. At some point, murder was struck from the list of appropriate mystery topics for juveniles and I’m not sure when it was added back into the mix (I’d suspect the 70s, and am genuinely curious to start collecting Edgar winners to find out). At any rate, the boys do witness a murder, in nowhere near the visceral detail of the bloody brawl in book one. There’s no way anyone who has already read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer would be bothered by anything in this book.

Values: The final passage seems to indicate that the best virtues in life are intelligence and humility, with Twain’s lack of satiric bite making it easier to get a read on such things…maybe.

Role Models: Tom and Huck are good kids, and even though they’re a bit tired on this outing, neither one feels like a caricature of their worst qualities. This is a nice note to go out on and is possibly the only reason this installment might be worth reading – although if you take my advice and skip all of the sequels, you’ll never have that problem in the first place.

Educational Properties: Nothing occurs to me.

End of Guide.

With that I conclude my first series for the WCC. From the start it wasn’t at all what I was expecting, but the complete Tom Sawyer was oddly endearing. As for Mark Twain, he only wrote one other novel that was intended for a juvenile audience – The Prince and the Pauper, which I have acquired a copy of and plan to review within the next few months.

Up Next: December, and to honor the Christmas spirit I will try to keep all reviews on books with a hopeful outlook (since I really don’t have enough Christmas-themed books for an entire month). So up next is Lloyd Alexander with a short novel in praise of the human condition.

Title: Anne of Windy Poplars (Anne Novels #4)

Title: Anne of Windy Poplars (Anne Novels #4)

![Image result for cold comfort farm book penguin]](https://www.penguin.co.uk/content/dam/prh/books/604/60407/9780241418895.jpg)