A history of Holland, a tour guide of the same and a novel all rolled into one. It has its flaws, but perhaps they reflect more poorly on we the modern audience than on the book itself.

Title: Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates

Title: Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates

Author: Mary Mapes Dodge (1831-1905)

Original Publication Date: 1865

Edition: Dover Publications, Inc (2003), 276 pages

Genre: Sentimental fiction.

Ages: 11-14

First Line: On a bright December morning long ago, two thinly clad children were kneeling upon the bank of a frozen canal in Holland.

The Brinkers are the poorest family in their Dutch village, ever since the terrible day when father Raff Brinker fell from a dike, struck his head and was brought home a lunatic – an event which coincided with the arrival of a mysterious watch and the disappearance of the family’s life savings, rendering the Brinkers destitute. It’s been ten years but young Hans Brinker is determined to earn money and hire the finest doctor in Holland to attempt a cure. All the other boys and girls in the village are more excited about an upcoming race whose prize is a pair of silver skates, but Hans and his sister Gretel possess only wooden skates and could never hope to compete. A group of local boys are about to set off on a skating tour of Holland and Hans sees them off with a message to the doctor to please hurry, for his father has taken a turn for the worse…

Hans Brinker is a Victorian novel, perhaps even quintessential of all those tropes and styles now associated with that age. You’ll find the worthy poor, prolonged suffering rewarded by a sentimental conclusion, the long arm of coincidence, high culture and lengthy digressions. This is a challenging book to read, and impossible for a child to enjoy unless they have been raised on the more accessible 19th Century classics. There are ample rewards to be had, especially for homeschooling families, but fair warning must be given.

Mary Mapes Dodge had never been to the Netherlands when she wrote Hans Brinker, but she knew many Dutch immigrants to America and did scrupulous research on Dutch landscape, culture and history, crafting a novel so accurate that it actually became a rare American novel of the time period to become popular overseas, while at home it outsold all but Charles Dickens himself. Hans Brinker became an undisputed children’s classic, and Dodge contributed to children’s literature in another way by becoming the editor of St. Nicholas magazine. She took this job very seriously and attracted great writers to the magazine, serializing Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy, Alcott’s Eight Cousins, Kipling’s Jungle Book and Twain’s Tom Sawyer Abroad.

Dodge’s importance to the field should not be overlooked; however, her one great novel was an odd mix of genres. The dramatic tale of the Brinker family had to share time with the sights and sounds of Holland, and since Hans and his family were far too poor to be traveling anywhere, Dodge had to devise a way to get the story out of the small town of Broek and into the great cities of Amsterdam and Haarlem. Her solution was to cut the story of Hans in half and give the middle portion of the book over to a skating tour, even adding the English boy Benjamin Dobbs to ensure that customs and monuments would receive naturalistic explanations within the text.

The skating portion is somewhat hard going for the modern reader, but the book-ending plot is designed to captivate the audience and still succeeds. The Brinkers live in dire poverty and although they are symbols of the virtuous poor, Dodge is willing to dive surprisingly deep into their inner lives. They feel real and developed, down to the smallest details like the slight religious schism between Dame Brinker and her very Protestant children, who are shocked when she considers praying to Saint Nicholas. The Dutch are not demonstrative in their affections, and thus the difference between “thee” and “thine” is of great importance to them. His mother had said “thee” to him, and that was quite enough to make even a dark day sunny. Gretel is burdened by tremendous guilt because she was only an infant when her father went crazy; having never known the real man, she is incapable of loving him the way her mother and Hans do. Even Dame Brinker is depicted as a real woman who had a life before her children were born, rather than a static mother figure. She remembers her lost husband with fondness but has carried a heavy burden which Hans is only just old enough to help with:

“When you and Gretel had the fever last winter, and our bread was nearly gone, and I could earn nothing, for fear you would die while my face was turned, oh! I tried then! I smoothed [Raff’s] hair and whispered to him soft as a kitten, about the money–where is was, who had it? Alack! He would pick at my sleeve and whisper gibberish till my blood ran cold. At last, while Gretel lay whiter than snow and you were raving on the bed, I screamed to him–it seemed as if he must hear me–‘Raff, where is our money? Do you know aught of the money, Raff? The money in the pouch and the stocking, in the big chest?’ But I might as well have talked to a stone. I might as–“

The mother’s voice sounded so strange, and her eye was so bright, that Hans, with a new anxiety, laid his hand upon her shoulder.

“Come, Mother,” he said, “let us try to forget this money. I am big and strong. Gretel, too, is very quick and willing. Soon all will be prosperous with us again.”

The family is very genuine, and this creates immediate interest in their plight. Dodge also weaves together several compelling questions around them. Will they find the money – and where on earth was it? Can Raff Brinker by cured? What’s up with the pocket watch? Who will win the race for the skates? With these looming mysteries waiting in the wings, Dodge goes in for a cliffhanger: It was a scream–a very faint scream! She then drops the plot entirely for 30 pages, at which point the Brinkers are revisited just long enough to resolve the scream incident and then are abandoned for a further 90 pages while Dodge shifts her focus to happy children on holiday.

The biggest problem with the resultant skating tour is that it is comprised of boys who are almost entirely removed from the main plot – only the leader, Peter van Holp, has any meaningful interaction with Hans, and that only happens after the party sets out. The tour also suffers from having one too many boys in tow, leaving me even at the end struggling to differentiate between Lambert and Ludwig. However, these problems being set aside, there’s actually a lot to enjoy about this portion of the novel, especially if you’re a history buff.

The 120 pages of the tour are a schoolbook tucked inside a novel. As such, it’s perfect for homeschoolers, or for anyone who wants to study Dutch history in a broader European context. Hans Brinker is a very cultured book, packed with references to explore. Dodge expects young readers to know who Handel was and to care about his visit to Haarlem, while her reference to Charles the First anticipates that children will either know or seek out further info on their own, as it brings up more questions than answers: A fresco features a number of family portraits, among them a group of royal children who in time were orphaned by a certain ax, which figures very frequently in European history. These children were painted many times by the Dutch artist Van Dyck, who was court painter to their father, Charles the First, of England. Beautiful children they were. What a deal of trouble the English nation would have been spared had they been as perfect in heart and soul as they were in form!

I read Hans Brinker as a kid, and since I never bothered to look up context for the books I read, I found it incredibly tedious. One must be willing to engage with the text or it turns into so much white noise, while the frustrated reader waits for something to happen. There are some scattered dramatic incidents along the tour, including an attempted robbery, and a surprising amount of humour (I was astonished to find a precursor to Monty Python’s Cheese Shop Sketch, in which Peter orders various foodstuffs at an inn only to be continuously told they’ve run out), but the pace is leisurely. The main purpose of this book is to transmit culture, and so it is atmospheric, descriptive and dense with Dutch inventors, physicians, painters and war heroes. It’s worth noting that English Ben squabbles with his Dutch cousin over which of their homelands is superior, yet their shared patriotism actually seems to knit them closer together rather than drive them apart.

Lambert: “I saw much to admire in England, and I hope I shall be sent back with you to study at Oxford, but take everything together, I like Holland best.”

“Of course you do,” said Ben in a tone of hearty approval. ” You wouldn’t be a good Hollander if you didn’t. Nothing like loving one’s country.”

The most famous part of Hans Brinker is actually far removed from both the A and B plots (or even the C plot surrounding the race). It is the famous story of the Dutch boy who stuck his finger in the hole in the dike and saved his town. This incident is a folktale facsimile which is apparently based on nothing, but Dodge makes it feel so credible that she convinced whole generations this was an old story – despite appearing in the text only as an English school lesson. It took on a life of its own, and Dutch Genealogy did an interesting article on the topic.

Of course, it’s just one more in a sea of digressions in this sprawling, thoughtful novel. Hans Brinker became an American children’s classic well before Tom Sawyer had appeared and a year before Little Women was published in book form, yet it has lost out to them both and is today rather difficult to recommend. The lack of streamlining which adds to the charming content of the book is now seen as a hindrance. While some aspects of the writing have dated very badly (most notably the climactic race sequence, which reads like closed-captioning in places) even at its best Hans Brinker feels like a novel whose time has passed. It makes me sad, but I’m not the one to judge, given that everything which Hans Brinker offers of interest, pathos and entertainment completely passed me by as a child. May other families have more luck.

See Also: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which also contains challenging prose but is far more modern in its commitment to entertainment rather than education.

Around the World in Eighty Days, another Victorian tour guide with endless asides, yet its digressions actually propel the ridiculous plot along rather than hinder it.

Parental Guide

Violence: The most memorable portion of the story concerns the lunatic father and the family’s wretched state of poverty, including an incident in which Raff seizes his wife and holds her so near the fire her dress begins to burn, laughing all the while.

Another incident occurs on the skating trip, wherein the boys count their money in an inn’s sitting room only to have one of the other patrons sneak into their room by night, armed with a knife. The boys overpower him and the episode is played as a schoolboy adventure.

Values: The book is laced with them, from family loyalty to noble suffering – for the Brinkers, begging is never an option. Education, care of the poor, Christian piety, humility and hard work all get their due.

This bit sums up much of the era’s outlook on what a boy should be, when Peter’s group realise they’ve lost their money purse and have to return home without food. A surly boy, Carl, says “Well, I see no better way than to go back hungry.”

“I see a better plan than that,” said the Captain.

“What is it?” cried all the boys.

“Why, to make the best of a bad business and go back pleasantly and like men,” said Peter, looking so gallant and handsome as he turned his frank face and clear blue eyes upon them that they caught his spirit.

Role Models: Hans, Gretel and a variety of other children are all virtuous, with character flaws given only to Carl and a couple of girls too proud to play with Gretel – all of whom are hinted to have a harder time in adulthood because of their lack of noble principles.

Educational Properties: Fairly well demonstrated already. Besides cultural and military history, there’s also plenty of descriptions of the region’s landscape and how human engineering and endeavor wrested the land away from the sea. Of course, all of its potential is useless if it fails to engage a modern audience, so make sure its a good fit for your family.

End of Guide.

Mary Mapes Dodge has a very short bibliography, of which only this novel is remembered. Her life’s work was St. Nicholas magazine, and between that and Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates she did a great deal to improve what was still a very new market. My work here is done and I’m glad I took the time to revisit this.

Up Next: A lengthy and regrettable hiatus for personal reasons.

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families.

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families.

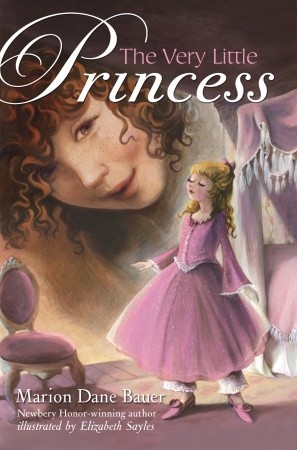

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man