It derailed the Great American Novel and it was totally worth it.

Title: The Prince and the Pauper

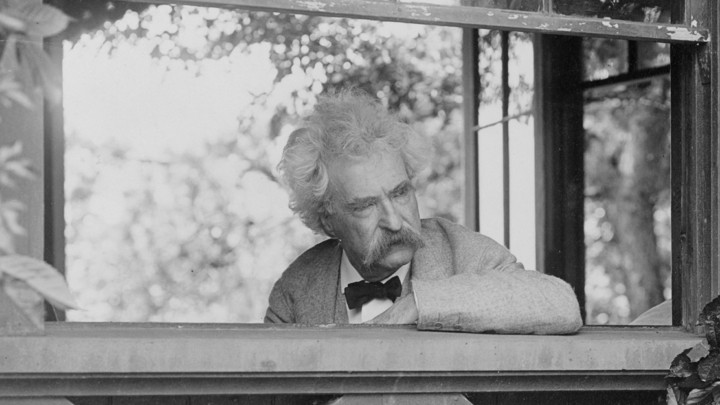

Author: Mark Twain (1835-1910)

Illustrator: Uncredited

Original Publication Date: 1881

Edition: Harper and Brothers Publishers (1909), 281 pages

Genre: Historical fiction. Adventure.

Ages: 10-14

First Sentence: In the ancient city of London on a certain autumn day in the second quarter of the sixteenth century, a boy was born to a poor family of the name of Canty, who did not want him.

As King Henry VIII’s health fails, a fateful meeting takes place between his son and heir, Edward VII, and a pauper named Tom Canty. The boys switch costume, marveling at their strangely identical appearance, but before they can change back, they are mistaken one for the other and Prince Edward is thrown from the palace on his ear while Tom is installed in his place. Edward must now venture through the underbelly of Tudor society, seeking someone to believe his claims, while Tom futilely insists that he is not the true heir to a court that can only maintain that the prince has gone mad. When King Henry dies, preparations for the coronation begin, but how will the prince ever regain his rightful place?

Mark Twain revolutionized American literature with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and its groundbreaking use of wholly accurate and authentic vernacular. His characters spoke in slightly different dialects depending on their location, class and race. He took far greater pains with the writing than he did with the plot, and it shows in his lazy sequels, where the accent work turns plain and inconsistent. However, in every one of those books he had an advantage: he was an American who’d grown up and spent years traveling and working in the south. While he visited England, it was clearly not long enough to learn anything about the overwhelming variety of accents to be found there. Everyone in The Prince and the Pauper speaks an identical version of ye olde English. Here’s the prince begging the pauper’s villainous father to believe that he is not Tom Canty:

“Oh, art his father, truly? Sweet heaven grant it be so–then wilt thou fetch him away and restore me!”

“His father? I know not what thou mean’st; I but know I am thy father, as thou shalt soon have cause to–“

“Oh, jest not, palter not, delay not!–I am worn, I am wounded, I can bear no more. Take me to the king my father, and he will make thee rich beyond thy wildest dreams. Believe me, man, believe me!–I speak no lie, but only the truth!–put forth thy hand and save me! I am indeed the Prince of Wales!”

Neither of the titular characters indulge in a second’s worth of masquerade. They both stand by their true identities, and yet the boy from Offal Court with only his feet for transport and the sequestered son of the King of England apparently speak as identically as they look. No Englishman would have written this plot (or if he did, he would choose an “exotic” locale like Ruritania to set it in). Twain grounds his flight of fancy amidst real historical events, but I don’t even want to criticize him for this. The Tom Sawyer books were not exactly bastions of realism either, and The Prince and the Pauper departs altogether into the realms of the fairy tale – a style which Twain does a great job with.

As a fairy tale, it’s properly dark, suited for those children who’ve grown up with Grimm, Andersen and other storytellers of good cruelly set upon before it can triumph. Twain’s inspiration seems to have stemmed in part from a desire to draw attention to the excessive punishments of the Tudor era, and as such his prince finds himself lost amid beggars, thieves and vagrants. What’s odd is that, unlike in the Tom Sawyer series, Twain wears his heart on his sleeve here, appearing in genuine earnest upon his subject. He offers few bon mots, but some of his loveliest writing, as when the prince (now king) finds shelter in a barn and friendship with a calf.

The king was not only delighted to find that the creature was only a calf, but delighted to have the calf’s company; for he had been feeling so lonesome and friendless that the company and comradeship of even this humble animal was welcome. And he had been so buffeted, so rudely entreated by his own kind, that it was a real comfort to him to feel that he was at last in the soiciety of a fellow-creature that had at least a soft heart and a gentle spirit, whatever loftier attributes might be lacking. So he resolved to waive rank and make friends with the calf.

…

Pleasant thoughts came at once; life took on a cheerfuler seeming. He was free of the bonds of servitude and crime, free of the companionship of base and brutal outlaws; he was warm, he was sheltered; in a word, he was happy. The night wind was rising; it swept by in fitful gusts that made the old barn quake and rattle, then its forces died down at intervals, and went moaning and wailing around corners and projections–but it was all music to the king, now that he was snug and comfortable; let it blow and rage, let it batter and bang, let it moan and wail, he minded it not, he only enjoyed it. He merely snuggled the closer to his friend, in a luxury of warm contentment, and drifted blissfully out of consciousness into a deep and dreamless sleep that was full of serenity and peace. The distant dogs howled, the melancholy kine complained, and the winds went on raging, whilst furious sheets of rain drove along the roof; but the majesty of England slept on undisturbed, and the calf did the same, it being a simply creature and not easily troubled by storms or embarrassed by sleeping with a king.

Twain uses an interesting tactic for the historical aspects included – where his interest in description flags, he simply excerpts from other chroniclers such as Leigh Hunt; educating his public while saving time. I guess that never caught on. It does disrupt the story a little bit, but it adds plenty of detail, especially of the resplendent pickle Tom Canty’s in.

Tom’s plotline is given less space, which is fitting since it’s considerably less dramatic. Unlike the Tom Sawyer books, whose plotting range from ramshackle to insane, The Prince and the Pauper is tightly woven. Tom Canty remains stationary, and the looming false coronation provides a natural venue for the finale, devoid of excessive coincidence.

Most of the secondary characters are only there to help or hinder the two boys, with the exception of Miles Hendon, a brave musketeer-styled nobleman who was wrongfully dispossessed and seeks restoration. Miles sees the good qualities in what he takes for a delusional beggar-boy, and so offers his protection. Although unconvinced by Edward’s assertions, Miles plays along, hoping to cure the boy of his madness and make him his ward. To this end, Miles becomes “a knight of the Kingdom of Dreams and Shadows” as the unlikely pair brave the mean streets of Tudor England together, and when separated, always find each other again.

The young prince does turn out to be every bit the equal of Miles for bravery. I had assumed going in that Edward would be the lesser of the two boys, stuck-up and ready for humbling, but he is so wholly principled and virtuous that Twain accidentally makes a case for monarchy through his example. Obviously, the plot couldn’t begin without the pair being rather dimwitted, but once the prince is cast into the streets things really get into gear. As Tom Canty’s abusive father and grandmother drag the prince “home” for a beating, the boy’s mother attempts to intervene and the prince’s mettle is revealed for the first time:

A sounding blow upon the prince’s shoulder from Canty’s broad palm sent him staggering into goodwife Canty’s arms, who clasped him to her breast, and sheltered him from a pelting rain of cuffs and slaps by interposing her own person.

The prince sprung away from Mrs. Canty, exclaiming:

“Thou shalt not suffer for me, madam. Let these swine do their will upon me alone.”

This speech infuriated the swine to such a degree that they set about their work without waste of time.

From this time forward, the prince shows loyalty to those as give him aid, compassion for the unjustly punished, contempt for the base and crooked, and obstinence in the face of disbelief. Trained in the art of the sword, he makes short work of boy thieves, and when captured by a gang of hoodlums, he refuses to improve his position by assisting in their plots to beg and steal.

Tom Canty is less sure of his moral compass. With less to lose, he finds himself going along with the masquerade he’s been forced into. He doesn’t like it but he adapts. Even here, the theme of justice asserts itself when Tom presides over a passing sheriff’s prisoners, bringing them into the palace to decide their fates. This culminates in some of the only comedic material in what is, for Twain, a thoroughly dramatic tale. Tom hears the accusation of witchcraft and storm-summoning levied against a mother and daughter:

“How wrought they, to bring the storm?”

“By pulling off their stockings, sire.”

This astonished Tom, and also fired his curiosity to fever heat. He said, eagerly:

“It is wonderful! Hath it always this dread effect?”

“Always, my liege–at least if the woman desire it, and utter the needful words, either in her mind or with her tongue.”

Tom turned to the woman, and said with impetuous zeal:

“Exert thy power–I would see a storm!”

There was a sudden paling of cheeks in the superstitious assemblage, and a general, though unexpressed, desire to get out of the place–all of which was lost upon Tom, who was dead to everything but the proposed cataclysm.

I could continue pulling quotes from this book all day, and I can well understand why Twain found this story more compelling than Huckleberry Finn. Throughout The Prince and the Pauper it seems as if he actually likes his characters – which I’m not sure can be said about any of his sequels to Tom Sawyer. Because it’s still written by Twain, there are occasional moments where his snideness gets the better of him, as when, after describing the engineering marvel of London Bridge and its remarkably self-sufficient community, he caps off with this statement: It was just the sort of population to be narrow and ignorant and self-conceited. However, that aspect of his writing is kept on a short leash here and not allowed to sprawl in every direction. The writing is wonderful, the plot is entertaining and though parts of it are very intense, that is compensated by the ever-present ideal of goodness. It is an undoubted children’s classic.

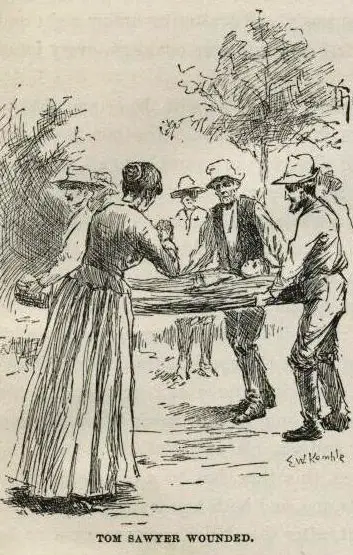

See Also: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Parental Guide.

Violence: Beatings were a part and parcel of the era, and the prince sustains a few. Several of the vagabonds he falls in with have missing ears and there are descriptions of other medieval punishments, from whipping to getting boiled alive. However, these are mostly second-hand accounts. There are only two sequences which directly affect the prince, and both have a similar intensity to the famous murder in Tom Sawyer. One occurs when two women are burned at the stake, with their relatives forcibly restrained from throwing themselves on the pyre, and the prince looking away in horror. Twain focuses only on the reaction of the onlookers, not on what’s happening to the condemned women, but it’s still extremely dark.

The other notable sequence is an abrupt shift into full-fledged horror tropes, when the prince seeks shelter with a hermit. The hermit turns out to be a thoroughly deranged Catholic, who, upon discovering that he has King Henry’s son in his power, decides to truss him up while he sleeps. His methodical arrangements (and Twain’s choice language) make the whole scene that much more creepy.

The old man glided away, stooping, stealthily, catlike, and brought the low bench. He seated himself upon it, half his body in the dim and flickering light, and the other half in shadow; and so, with his craving eyes bent upon the slumbering boy, he kept his patient vigil there, heedless of the drift of time, and softly whetted his knife, and mumbled and chuckled; and in aspect and attitude he resembled nothing so much as a grizzly, monstrous spider, gloating over some hapless insect that lay bound and helpless in his web.

Values: Packed full, unusually for Twain. There’s a great deal of focus on noble characteristics, the quality of mercy and the value of education. This is also a precursor to A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, engaged at least in part around the cruel and unusual punishments of Tudor England, though here lacking the American alternative.

Role Models: Between Edward, Tom and Miles, practically every masculine virtue is exemplified, among them honor, honesty, strength, fidelity, principal, integrity, compassion, sacrifice and protectiveness. Twain dedicated the book to his own daughters, and it’s rather sweet to see this less jaundiced side of the man.

Educational Properties: This book furnishes a very detailed view of Tudor England and with so much focus on criminal law, social stratification, royal customs and historic London, it’s a great boon to homeschoolers, not even taking into account its highly advanced diction.

End of Guide.

And with this I have completed Mark Twain’s juvenile bibliography, ending on a high note indeed.

Title: Stormy, Misty’s Foal (Misty #3)

Title: Stormy, Misty’s Foal (Misty #3)

Title: The Midnight Fox

Title: The Midnight Fox

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated.

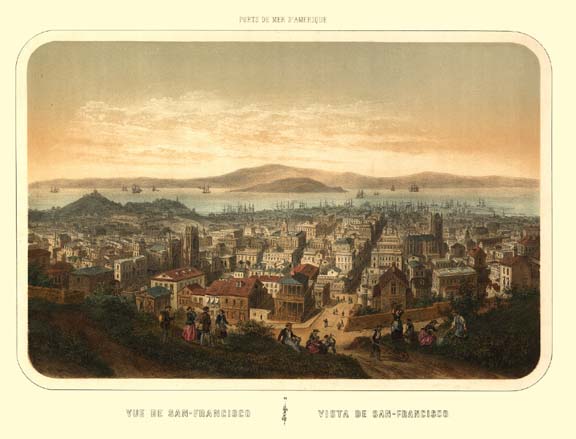

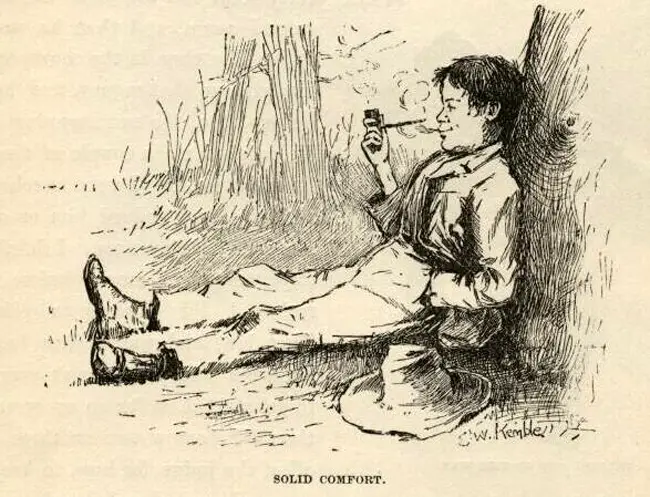

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated. Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Shane

Title: Shane