A glorious Victorian travel extravaganza, more exciting than it has any right to be.

T itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

Author: Jules Verne (1828-1905)

Translator: George Makepeace Towle (1819-1900)

Original Publication Date: 1872

Edition: Dover Publications, Inc. (2015), 170 pages

Genre: Adventure. Humour.

Ages: 11-15

First Sentence: Mr. Phileas Fogg lived, in 1872, at No. 7, Saville Row, Burlington Gardens, the house in which Sheridan died in 1814.

Inveterate whist-player Phileas Fogg takes up a wager that he can make it around the world in eighty days, a calculation considered technically accurate but impossible to carry out, given that even a single delay of the sort frequent in travel (breakdowns, weather) would render the entire journey a failure. Fogg is honour-bound and OCD enough to attempt it though, and off he goes with his freshly-hired French manservant Passpartout on a wild spending spree that takes them from the Suez Canal, across India, along the coast of China and on a madcap journey across the barbarous land that is…the United States of America. Fogg never loses his cool but unluckily for him, dogged Detective Fix is on his trail, determined to bring him to justice for a bank robbery that took place right before Fogg left on his globetrotting quest – a very suspicious coincidence given the large suitcase full of cash he carries with him. Will Fogg win his bet? Will Fix get his man? Will Passepartout have a nervous breakdown before the finish line?

It turns out that Around the World in Eighty Days is an absurdly charming novel, centered on a voyage so far-fetched that it’s truly impressive how Jules Verne is able to make it seem so incredibly urgent that Phileas Fogg win his bet. It feels certain that Fogg will triumph in the end, yet the odds remain so impossible that pages are turned with increasing speed to see how he will outmaneuver each problem on what becomes the world’s biggest obstacle course. Helping the reader in this are the short chapter lengths, always between three and six pages in the Dover edition, which take full advantage of the original newspaper serial format that Verne wrote it for.

The sight-seeing is depicted with full relish, regardless of Fogg’s complete disinterest in all matters unrelated to his time table. Mr. Fogg, after bidding good-bye to his whist partners, left the steamer, gave his servant several errands to do, urged it upon him to be at the station promptly at eight, and, with his regular step, which beat to the second, like an astronomical clock, direct his steps to the passport office. As for the wonders of Bombay–its famous city hall, its splendid library, its forts and docks, its bazaars, mosques, synagogues, its Armenian churches, and the noble pagoda on Malabar Hill with its two polygonal towers–he cared not a straw to see them. He would not deign to examine even the masterpieces of Elephanta, or the mysterious hypogea, concealed south-east from the docks, or those fine remains of Buddhist architecture, the Kanherian grottoes of the island of Salcette. As you can tell, this novel has absolute confidence in its references and encourages armchair traveling – this would have been an enormous part of its original appeal to readers of all ages and there’s less reason than ever to be intimidated by Verne’s exotic travelogue in this day and age.

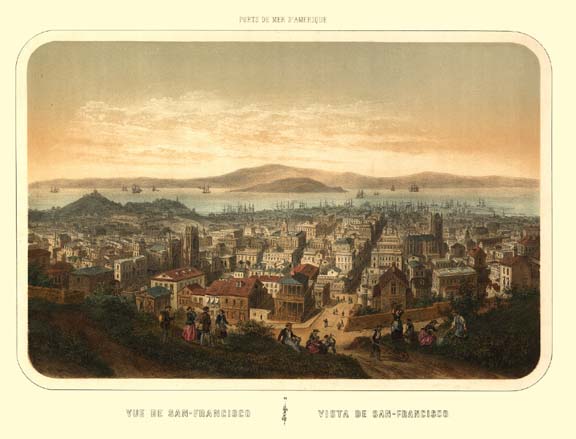

What’s especially amusing if you’re part of the American audience is his depiction of the U.S. as a vast and violent land where political elections are violent brawls in the street and the Sioux are accustomed to attacking trains, yet commerce eventually transforms even the wildest frontier towns into bustling hives of trade. A first glimpse of San Francisco: From his exalted position Passepartout observed with much curiosity the wide streets, the low, evenly ranged houses, the Anglo-Saxon Gothic churches, the great docks, the palatial wooden and brick warehouses, the numerous conveyances, omnibuses, horse-cars, and upon the sidewalks, not only Americans and Europeans, but Chinese and Indians. Passepartout was surprised at all he saw. San Francisco was no longer the legendary city of 1849,–a city of banditti, assassins, and incendiaries, who had flocked hither in crowds in pursuit of plunder; a paradise of outlaw, where they gambled with gold-dust, a revolver in one hand and a bowie-knife in the other: it was now a great commercial emporium.

All of this colorful material would be little more than an opinionated encyclopedia were it not for the comic trio that traverse the pages. Phileas Fogg is something of a prototype for the cool-headed British man of action, jet-setting (as it were) with watch in hand, impeccable manners and rock-solid stoicism. He is the man who conquers time through sheer logic and indominability:

“Mr. Fogg this is a delay greatly to your disadvantage.”

“No, Sir Francis; it was foreseen.”

“What! You knew that the way-“

“Not at all; but I knew that some obstacle or other would sooner or later arise on my route. Nothing, therefore, is lost. I have two days which I have already gained to sacrifice. A steamer leaves Calcutta for Hong Kong at noon, on the 25th. This is the 22nd, and we shall reach Calcutta in time.”

There was nothing to say to so confident a response.

Serving as foil, there is the comical manservant Passepartout, who begins a baffled underling but comes to see his employer as a great man. However, he never does share Fogg’s confidence that all obstacles can be overcome. A retired acrobat, his athleticism comes in handy on the road, while his folly creates many of the obstacles that Fogg must conquer. To keep the reader from seeing Passepartout as a millstone that Fogg should abandon on route, Verne takes care to give each mishap a fresh extenuating circumstance.

Lastly, there is Detective Fix, who is the most complicated and interesting of the three as he is the most changeable in his pursuit of what he believes to be the world’s most eccentric bank robber. He is a droll variation on the great Javert archetype as he morphs from friend to foe and back again, set on his purpose but increasingly perplexed by Fogg’s behaviour and therefore always having to question the nature of the supposed rascal he’s pursuing. Fix is a very dynamic character, such that Around the World doesn’t really get good until his appearance in Suez.

Rounding out the cast is the late addition of Aouda, a beautiful Indian of the highest caste whom Fogg and Passepartout rescue from a passing “suttee.” She’s as fair as a European, has received a full European education in Bombay, is a match for Fogg in stoicism and knows how to use a pistol. Fogg and Passepartout end up carting her all the way round the world and she holds her own in the endeavor – girl even knows how to play whist. With this honorary European along for the ride, everything is in place – romance, adventure, comedy, thrilling suspense, twists of fortune and ever-shifting scenery from elephant rides to opium dens…

Around the World in Eighty Days is a lightweight volume, all the more surprising considering the troubled times it was written in. Verne kept a stiff upper lip as well as any Englishman by crafting this wild caper in the midst of the Franco-Prussian War. It doesn’t feel like a children’s classic as we would think of it, but this would be a boon to homeschooling families as Verne touches on everything from Victorian world history to scientific innovation to mathematical calculations. The casual historicity extending from the first sentence of this volume, along with its elegant sentence structure, generous vocabulary and competent adult heroes are not things you’ll find represented in most modern YA. This in itself demonstrates why the old books are irreplaceable and well worth adding to your children’s library. Around the World in Eighty Days is also worth reading for any adult fans of old-school adventures, as it is a delight through and through.

See Also: The Scarlet Pimpernel, another example of rich language matched with a plot that is accessible to younger readers, thus bridging the gap between children’s classics and grown-up ones.

Parental Guide, with some spoilers.

Violence: The concept of sati is introduced, as is that of dueling – though neither event takes place, it’s clear what would happen if they did. There’s a brawl in San Francisco, but it isn’t until the Sioux attack the train that we get some really descriptive bloodshed: Twenty Sioux had fallen mortally wounded to the ground, and the wheels crushed those who fell upon the rails as if they had been worms. Later, after the battle: All the passengers had got out of the train, the wheels of which were stained with blood. From the ties and spokes hung ragged pieces of flesh. As far as the eye could reach on the white plain behind, red trails were visible.

Values: Pure Victorian Age goodness here. Logic and strength defeat every obstacle, engineering is a continuous marvel and honor is held in such high regard that to back out of a wager is impossible.

The Victorians believed in hierarchies of civilization and much of that confidence and willingness to judge other cultures is displayed here, which may not be to every taste. Verne refers to those who willingly participate in sati as stupid fanatics, while Aouda, who had to be drugged to ensure her cooperation in the matter, is a charming woman, in all the European acceptation of the phrase. Far from being too harsh a judge of the foreign climes his heroes traverse, Verne is remarkably tolerant – at one point even embarrassingly naive, giving a passing mention to the savage Papuans, who are in the lowest scale of humanity, but are not, as has been asserted, cannibals. Sorry, Monsieur Verne, they really, really are.

One very pleasant surprise herein is the treatment afforded animals. Older books have a tendency to be callous on this subject, but Verne’s ideal gentlemen treat animals (and women, and servants) with every courtesy. The elephant Kiouri is purchased to make a crossing of the forests of India and is in the end made a gift (alongside the agreed payment) to the loyal Parsee who drove and tended the gentle creature.

Oh, and this is now the second children’s classic I have found about the great power of the bribe to overcome obstacles, and Verne acknowledges the importance of Fogg’s tremendous wealth. Up to this time money had smoothed away every obstacle. Now money failed.

Role Models: Fogg is eccentric but an impeccable gentleman through every trial. Passepartout is loyal and brave, and always looks for ways to be of help, especially after making mistakes. Aouda is equal to the task of winning the wager, can handle a firearm under duress and offers to marry Fogg rather than the other way around, but she’s never less than gracious and feminine – modern YA could learn something here. Even Fix has admirable qualities despite being essentially the villain. Verne also allows each of these characters a chace to salvage the expedition in successive eleventh hours, so no one is ever dead weight to the tale.

Educational Properties: The Extraordinary Voyages were conceived as a way to present the most up-to-date information available on all subjects of scientific knowledge in an entertaining framework. The books do not actually lose anything by being out of date, as they can act as both a spur and a grounding for researching modern theories and revelations. Around the World offers material on the history of transportation, scientific innovations for logistical quandaries. Logistics ties in to mathematics, calculations of speed, distance and the circumference of the earth. There is a wide range of geography covered and then global history and culture in the 1860s and 70s. A wealth of material for what is quite a short book, that is only one of fifty-four standalone books in this series. Though English language translations are renowned mainly for not doing justice to Verne’s vision, I should still think these Voyages an excellent resource. Bonus: If your family is bi-lingual French or committed to mastering the language, that regrettable problem can be bypassed.

End of Guide.

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated.

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated.

Up Next: My final post on E.B. White with his final children’s novel.

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

1919, leaving Baroness Orczy the clear originator of the “masked avenger” so widespread in 20th Century entertainment. Given how prevalent the trope has become, I have to wonder if anyone could possibly be surprised by the identity of the Scarlet Pimpernel anymore. Given how few characters are in the book, I also wonder when her original audience was expected to have it sussed out.

1919, leaving Baroness Orczy the clear originator of the “masked avenger” so widespread in 20th Century entertainment. Given how prevalent the trope has become, I have to wonder if anyone could possibly be surprised by the identity of the Scarlet Pimpernel anymore. Given how few characters are in the book, I also wonder when her original audience was expected to have it sussed out.