This book begins with a run-on sentence. Prepare yourself for a rant, because there will be no prisoners taken, nor will I be using any spoiler warnings in this review…

Title: One for Sorrow: A Ghost Story

Title: One for Sorrow: A Ghost Story

Author: Mary Downing Hahn (1937-)

Original Publication Date: 2017

Edition: Scholastic Inc. (2018), 293 pages

Genre: Horror. Fantasy. Historical fiction.

Ages: 10?

First Sentence: Although I didn’t realize it, my troubles began when we moved to Portman Street, and I became a student in the Pearce Academy for Girls, the finest school in the town of Mount Pleasant, according to father.

It’s 1918 and the Spanish Flu is making the rounds of America. Shy Annie Browne is new in school and on her first day is immediately “befriended” by Elsie Schneider, a lying, controlling, destructive little psycho whom all the other girls despise. Annie is prevented from making any other friends until Elsie is absent from school, at which point Annie is finally brought into the popular circle – and takes part in their ceaseless bullying of Elsie. There’s no doubt that Elsie brings it on herself, but she’s grossly outnumbered and Annie feels bad about her part in it (not that it stops her). Eventually, Elsie gets the flu and dies, only to return as an angry ghost with a particular grudge against Rosie, the leader of the clique, and guilt-stricken Annie.

Okay, so the writing in this book is absolutely horrible, beginning with the most brutally short paragraphs this side of a Guardian article. Sentences are clipped, descriptive prose is fleeting and the vocabulary is limited and therefore numbingly repetitive. Is this the style of today? If so, it’s been streamlined of everything that could possibly make reading a “chore.”

Just as I finished my oatmeal, Jane knocked on the door.

When I ran to meet her, she gave me a big hug. “Oh, I’m so glad you’re well enough to come back to school, Annie. I’ve missed you so much.”

“I’ve missed you, too.”

The prose is continually stuck at the level of early chapter books – and not even challenging ones at that. You’ll find more detailed verbiage in American Girl, Chet Gecko and Beverly Cleary stories for younger readers and that’s a death blow for this entire book. The concept – a ghost story kicked off by the Spanish Influenza at the end of the First World War – has so much potential, but it can’t be harnessed because the setting is never given any focus or weight. Hahn is a veteran writer; she’s been doing this since the 1980s and once won the Scott O’Dell award for historical fiction, but there’s no evidence here for why that would have ever been the case. Aside from the games girls played, the books they read and some basic info on wakes and horse-drawn hearses, there’s just nothing here. Maryland in 1918 is a vague backdrop for the ghostly plot, nothing more.

As far as the plot goes, Elsie’s ghost doesn’t appear until over 100 pages in – before that, One for Sorrow is a story about bullying, which means it should be character driven. It isn’t. Aside from Elsie and Rosie, almost none of the characters merit any physical description or personality. The clique of mean girls are only distinguishable by their degrees of guilt, with the “nice” ones (Annie and Jane) feeling more guilt and the “mean” ones (Eunice and Lucy) feeling less, with Rosie somewhere in the middle. Never mind that this sets up the phony idea that guilt is somehow a virtue; it can lead to virtue but just as easily to self-destruction. As such, none of these girls have any positive traits whatsoever. They are nasty, ill-mannered liars without a complete spine between them. Rosie comes up with a plan (inspired by the true story of Hahn’s mother) to get free sweets by going to wakes and pretending to know the dead people there. “We won’t be doing anything wrong,” Rosie said. “We’ll tell people how sorry we are, we’ll talk about how nice the dead person was, we’ll make the mourners feel better. That’s not taking advantage, that’s not lying.” And Annie more than once compares this horrid specimen to Anne Shirley, who never told a lie. But since most kids won’t (or can’t?) read Anne of Green Gables, I guess they’ll never know that.

As for Annie, she’s a complete drip with no spirit at all. One could be forgiven for assuming that she must improve at some point, being the protagonist and all, but you would be wrong. To the end she thinks (paraphrasing): “oh, why did I let Elsie make me do those terrible things?” She makes no effort to defeat Elsie’s ghost. She goes along with every stupid and cruel idea Rosie ever has, even one which nearly gets her killed, and then feels bad afterwards. She does not grow or alter through the book and never comes clean. When she stumbles upon a retired ghost hunter called Mrs. Jameson, it is by accident, and she simply follows all of Mrs. Jameson’s instructions thereafter with no agency of her own.

So much for the characters. The plot begins with children being mean (usually by shoving and screaming insults at one another) and once Elsie’s ghost appears it’s just round two of the same spiel for more tedious pages of screaming and shoving. Ghost Elsie is exactly the same as living Elsie, only with more power. This should be unnerving but it isn’t. For instance, Elsie possesses Annie and makes her do terrible things, but Annie doesn’t black out (which would heighten the suspense by adding mystery) or have enough personality to make the behavioral change feel horrifying (a la Tiffany Aching in A Hat Full of Sky). The writing continues to be frenetic and flat, and Elsie explains from the start what she intends to do to Annie, so there’s no chance for the situation to ever feel dreadful or uncanny: Alone except for Elsie, I found myself removing the flu mask from my bookbag and tucking it into Rosie’s. I didn’t want to do it, but I couldn’t stop. It was as if I were outside my own body, watching myself.

One for Sorrow is a ghost story that has no sense of the unearthly and no allowance for anything bigger than the individual. A Scooby-Doo hoax would feel more authentic to this novel’s worldview because while this is set in 1918, all of the characters are from 2017.

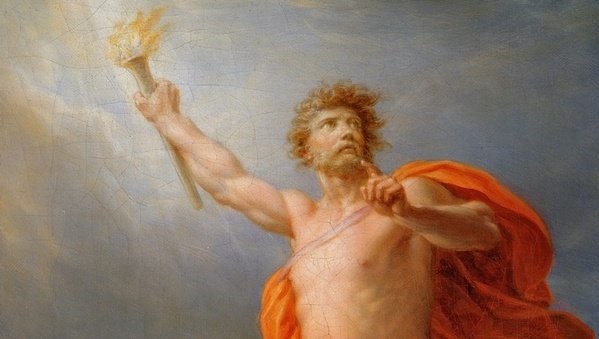

In 1918 a girl’s first thought about ghosts would involve the state of the soul, salvation and damnation. Annie would pray to God for aid and she would go to church – if for no other reason than the hope that Elsie couldn’t follow her there. But Annie doesn’t even think of any of those things, because Annie is from 2017. That’s why she mishears the phrase “at peace with the Lord” as “at the beach with the Lord” – because she’s never heard it before. She’s shocked at the notion of corporeal punishment because her parents and teachers also belong in 2017 (Miss Harrison, faced with a sea of screaming pupils disgracing her school’s orderly reputation, disciplines them by ending recess early). Muddying the waters are a couple of references to hell and the devil, which means Hahn wants us to think of these characters as Christian, even though they obviously aren’t.

So let’s try to assume that Annie and her entire social circle are the very height of the 1918 progressive movement. But just as there’s no spiritual element to her problem, there’s no historical one either – because guess what? Annie loves to read, so it really should occur to her that Elsie can’t be the world’s first ghost. It has to have happened before and there should be records, yet she does no research on spiritualists and ghost-hunters, and no one reading this book would gain from it any sense of the antiquity of hauntings. When Annie’s bad behavior gets out of hand, she’s sent to a convalescent home and it just so happens there’s a retired ghost-hunter on the premises. Mrs. Jameson drops hints that she’s an expert on the matter, but even at this stage there’s nothing bigger than the ghosts – in fact, Mrs. Jameson can’t “help” Elsie until she dies and becomes one herself. In other words, when Elsie causes Mrs. Jameson to fall and break a hip, it’s actually a good thing.

Lastly, although Elsie is clearly psychotic – revelling in every drop of pain she causes and before her death probably headed to a future abducting and murdering children – it turns out that she can only be defeated by empathy.

It’s not even genuine empathy. You know, the sort that would make this story less about the ghost and more about the life lessons the heroine learns about caring for others and standing up to bullies and whatnot. That would be corny but fairly typical. Instead, Mrs. Jameson flat-out instructs Annie to lie: “Be kind to her, earn her trust.” Annie loathes Elsie but pretends otherwise – and it’s the right thing to do. Elsie kills Mrs. Jameson – and it’s the right thing to do. Early on in the book, Elsie screams at Annie: “I’d give anything to have a mother like yours. It’s not fair that you have so much and I have nothing!” Herein lies the key to her defeat. She’s just an underprivileged child who wants her mommy and the whole book was a 200 page temper tantrum (culminating in the murder of a little old lady). It turns out that sympathizing with the motives of evil is what defeats it.

To be extra clear, Elsie does not show any mercy at the end of this book. She becomes “reachable” because she turns maudlin and self-pitying for a couple of minutes. She is not redeemed, but she gets everything she wanted, including a free ticket to the afterlife to reunite with her dead mother. She’s like Hannah in Thirteen Reasons Why, only she’s a literal ghost instead of tapes. She dies and is avenged. All of the adults feel sorry for her, all of the girls who wouldn’t be her friends are haunted by their actions and she never has to repent or live with any of her own choices.

The point of the Castle Project has always been to read as widely as possible in the field of children’s literature. I cannot proclaim the superiority of vintage options if I don’t read the modern alternatives. Well, here you go. On technical merits, One for Sorrow is abysmal. It is relentlessly unpleasant, philosophically poisonous and the bigger picture behind this book implies that speculative fiction in particular is on a steep decline. If there’s nothing bigger than our finite experience, if good and evil are relative based on the individual and if our entire history means nothing, we will be seeing more and more fantasies robbed of power and built on sand.

There was only one thing I appreciated about One for Sorrow and that was Hahn’s inclusion of many book titles which girls of the time would have read. After a while I began keeping a list, hoping that Hahn was sending some kind of message to her readers (she was born in the 1930s, so she has to be aware of what’s happened):

L.M. Montgomery – Anne of Green Gables; Anne’s House of Dreams

Johann D. Wyss – The Swiss Family Robinson

Wilkie Collins – The Moonstone; The Woman in White

Charles Dickens – The Pickwick Papers

Ouida – A Dog of Flanders

Zane Grey – Riders of the Purple Sage

Louisa May Alcott – Little Women

Booth Tarkington – Penrod; Seventeen; The Magnificent Ambersons

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow – ‘The Wreck of the Hesperus’

Victor Appleton – Tom Swift

Sir Walter Scott

Edgar Allan Poe

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Feast your eyes and think of what they call progress.

See Also: The Coffin Quilt by Ann Rinaldi. Set during the Hatfield-McCoy feud, this books contains plenty of southern gothic atmosphere, morbid and murderous occurrences, actual historical detail and period-accurate belief systems.

Parental Guide, just for fun.

Violence: You’ve got your dead people, your rotting ghost, and your screaming, shoving, fat-shaming and throwing things (these bullies don’t have very original material). Without atmosphere or subtlety, the disturbing horror content ranges from merely annoying to unpleasant. Spookiness can be fun. This was neither.

Values: Be nice! Lying makes people feel better, so it’s good! Empathize at all costs, even with psychos – because if you’re only nice enough, they’ll totally leave you alone!

There’s also a dropped plotline in which the girls hate Elsie for being German, which sets up a commentary on xenophobia that is never utilized because that’s not really why they hate her. It’s just an extra way to insult her.

Role Models: Everyone is horrible. Oh and Annie gets a concussion from sledding. Headfirst. At night. In a cemetery. Just thought I’d mention it.

Educational Properties: If you or yours have already suffered through it, by all means hold a discussion on morality and the Spanish flu to try and make it worth your time. Otherwise, no.

End of Guide.

Mary Downing Hahn has written many ghost stories, and I can easily believe the ones from the 80s were better just because the trends in children’s publishing were healthier at the time. Judging an author from a single book is never entirely fair, but I have to admit that I’m sorely tempted to do so in this case.

Up Next: The vintage equivalent. An obscure Canadian choice from 1968 featuring another angry ghost girl. Let’s see how it stacks up, just as a nice note to go out on.

Title: A Stranger Came Ashore

Title: A Stranger Came Ashore

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: The Magic Snow Bird and Other Stories

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families.

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families. Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Stones are Hatching

Title: The Stones are Hatching

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Wild Western Thimbleberry

Wild Western Thimbleberry

Title: Time Cat

Title: Time Cat

Title: The Court of the Stone Children

Title: The Court of the Stone Children