A mildly meta curio spoiled by an ill-thought moral at the end. Not recommended.

Title: Wolf Story

Title: Wolf Story

Author: William McCleery (1911-2000)

Illustrator: Warren Chappell (1904-1991)

Original Publication Date: 1947

Edition: NYRB Children’s Collection (2012), 82 pages

Genre: Humor.

Ages: 4-6

First Sentence: Once upon a time a man was putting his five-year-old son Michael to bed and the boy asked for a story.

A father tucks his son into bed and the son naturally wants a story. After rejecting Goldilocks, Michael requests a new story and is soon “helping” his father make it more exciting by adding a fierce wolf called Waldo to the mix. On subsequent outings with Michael and his best friend Stefan the wolf story continues, despite the father’s boredom, until they reach a mutually satisfying conclusion.

Okay, so this book is nowhere near as meta as it probably sounds. The first two chapters do work quite well in that regard, as the story is constructed while the father and son’s relationship is being sketched out – mostly through the use of dialogue. It’s cozy and endearing, while also forming a humorous commentary on storytelling conventions:

And the man continued: “Once upon a time there was a hen. She was called Rainbow because her feathers were of many different colors: red and pink and purple and lavender and magenta–” The boy yawned. “–and violet and yellow and orange…”

“That will be enough colors,” said the boy.

“And green and dark green and light green…”

“Daddy! Stop!” cried the boy. “Stop saying so many colors. You’re putting me to sleep!”

“Why not?” said the man. “This is bed-time.”

“But I want some story first!” said the boy. “Not just colors.”

“All right, all right,” said the man. “Well, Rainbow lived with many other hens in a house on a farm at the edge of a deep dark forest and in the deep dark forest lived a guess what.”

“A wolf,” said the boy, sitting up in bed.

“No, sir!” cried the man.

“Make it that a wolf lived in the deep dark forest,” said the boy.

“Please,” said the man. “Anything but a wolf. A weasel, a ferret, a lion, an elephant…”

“A wolf,” said the boy.

The rapport between father and son creates a pleasantly homey vibe, so nostalgic that it seems pulled directly from McCleery’s own experiences telling bedtime stories to his son. However, the novel proceeds to take on a slightly different tone, as subsequent chapters take place on various Sunday outings, accompanied by Michael’s best friend Stefan – from then on it’s two against one as the boys hijack and control the story, reducing the early delightful tug of war. The wolf story is then continuously interrupted by forays into the wider world of 1940s New York:

“Do you mind if we have lunch in the park?” said the boy’s father to the boy’s mother. “Would you mind not having to fix lunch for us?”

“Oh, that would be terrible,” said the boy’s mother. “If I don’t have to fix lunch for you I will be forced to go back to bed and read the Sunday paper!”

Soon the man and the two boys were driving along the West Side Highway toward Fort Tryon Park. The boys could see freighters, tankers, ferry boats and other craft in the Hudson River. “Enemy battleships!” the boys cried, and raked them with fire from their wooden rifles. Sometimes the man had to speak sternly to the boys, saying, “Boys! Sit down! Stop waving those rifles around. Do you want to knock my front teeth out?”

The boys were very well behaved, and every time the man spoke sternly to them they would stop waving the rifles around, for a few seconds anyway.

As you can tell, McCleery has a fairly repetitive style and prefers to avoid using names or descriptions for his characters. The story is completely trivial and its lack of suspense probably works in favor of a young audience – the wolf story is constantly being treated as a game by the boys, cutting any build-up of suspense with interruptions. It’s packed with dialogue, onomatopoeia and exclamation points, and supposedly makes an enjoyable read-aloud (although I have some caveats in the Parental Guide). McCleery wrote plays for television and Broadway, which explains a lot about his style.

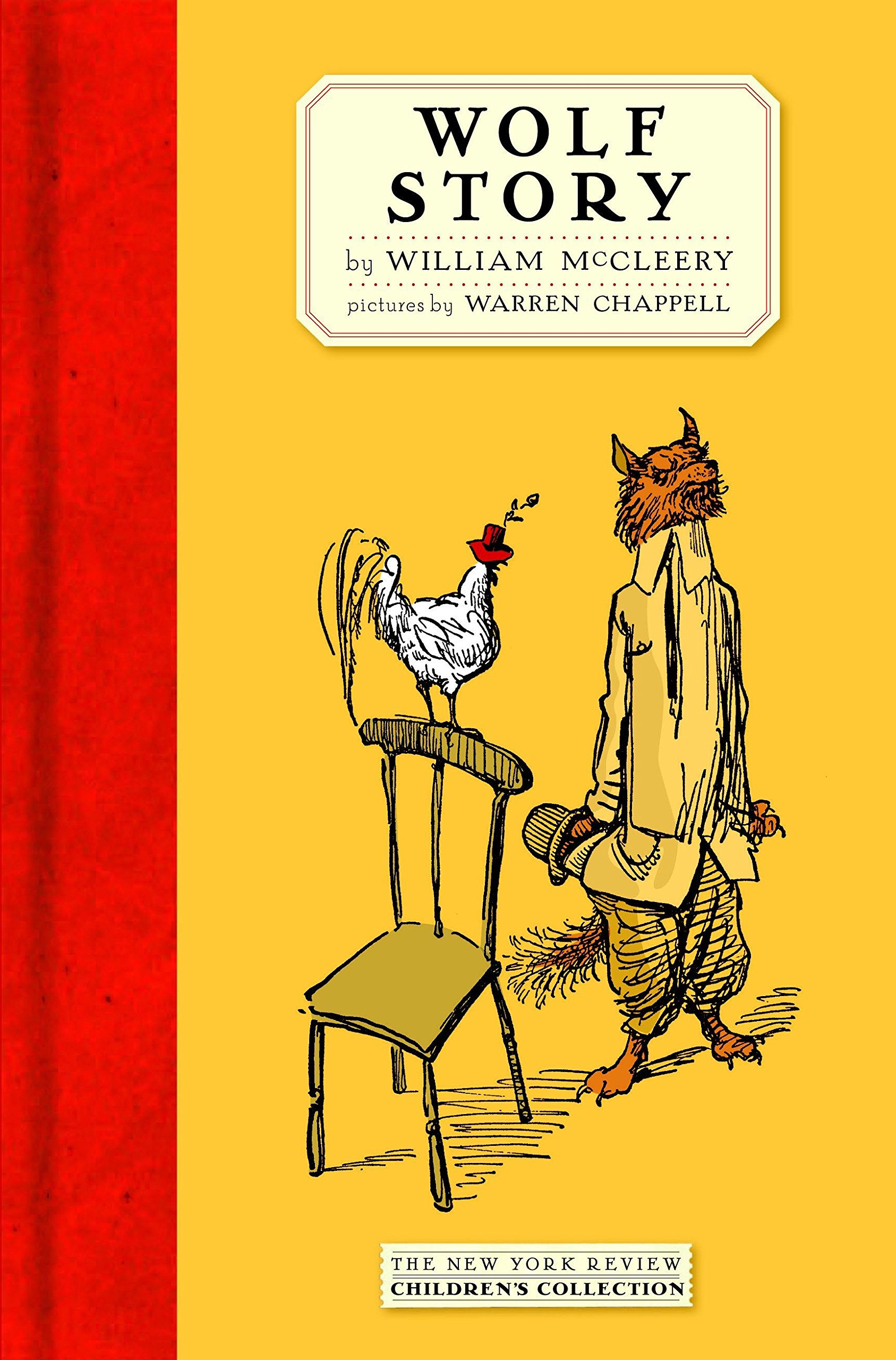

I would say that Wolf Story‘s greatest asset is its illustrator, Warren Chappell. Leaving the family wholly anonymous, he only illustrates the tale within the tale. Chappell takes McCleery’s dim-witted wolf and makes him hulking and villainous, yet absurd, while Rainbow the hen looks like she wandered in from Greenwich Village, sporting a debonair hat. Most charming of all are his medieval letters at the start of every chapter, with the wolf lurking behind them (it’s a pity the 10 chapters only opened with 5 individual letters).

Wolf Story is a very short book. It’s nicely packaged by NYRB and it seems to be well-received by modern parents – however, it doesn’t strike me as a lost children’s classic and I’m a little surprised it was chosen out of the sea of out-of-print stories waiting for a new lease on life. The plot is slight and gains little development, characters are thinly sketched, the glimpses of 1940s New York are all too brief and the writing is on the flat side. Also, the ending is a huge problem – the wolf story is based around a folktale motif, but if you enjoy the hard-headed sensibilities of classic folktales (where evil, selfishness and stupidity are punished in the end), you will probably find Wolf Story as much a letdown as I did. It looks good at the start but it wouldn’t make my list of vintage gems.

See Also: Stuart Little, another evocation of New York in the 40s, directed to the same basic age group (though the writing has way more style) and with eccentricities all its own…

And now a long Parental Guide for a short novel. Big spoilers for how the book ends.

Language: Quick heads up that there is one appearance of the word “damn,” which the father tries to dissuade his son from using, offering “darn” as a substitute – this book gets called a perfect read-aloud a lot, but I know there are parents who would prefer curse-free books for their six year olds.

Violence: It’s about as serious as a Road Runner cartoon. Five year old Jimmy Tractorwheel, the farmer’s son, wallops Waldo the Wolf with a baseball bat and all that’s missing from the scene are the circling birdies. Lots of threats of eating the hen or shooting the wolf but no one actually dies, leading to…

Values: …the father inserting an asinine moral when the farmer’s family finally capture Waldo. Jimmy Tractorwheel decides to try and reform Waldo after the wolf whines about how: “I never had no opportunities. I ain’t even been to school.” He’s still a wolf, but that’s forgotten about and social experimentation follows, which the father insists is absolutely successful: “So Waldo was locked up and every day Jimmy would come and ask him questions about how a wolf is treated by his parents and what makes him so fierce. The more Waldo talked about his fierceness the gentler he grew, until finally he was allowed out of the cage on a leash. Jimmy and Waldo wrote a book about wolves which was read by the farmers and the wolves in that part of the country and helped them to understand each other. They all became quite friendly and some wolves even worked on the farms, as sheepdogs.”

Michael actually tries to have Waldo revert to type and repay the farmer by stealing Rainbow again, but the father won’t have it and ends the story, which put me in mind of the quote by G.K. Chesterton: “For children are innocent and love justice, while most of us are wicked and naturally prefer mercy.”

Role Models: The father clearly intends Jimmy to be such. Since both the father and Jimmy literally advocate letting a fox wolf guard the hen house, they obviously aren’t very smart. The wolf himself has no redeeming qualities – he is murderous, doltish and cowardly – yet he gets off scot-free.

Educational Properties: Since this is a static novel about the joys of telling a dynamic story out of thin air, it could be used as an example of meta fiction for the young. You might also discuss the ending and explain that A: wolves are not tameable and B: pop psychology is not a panacea (and that’s just for starters). There are already too many people out there who think they live in a Disney movie. This is not helpful.

End of Guide.

This was William McCleery’s only work for young people, which means I have now completed his bibliography and I’m honestly relieved. Imagine what he’d have done with The Little Red Hen…

Up Next: Back to the story of Anne Shirley.

Title: Tom Sawyer Abroad

Title: Tom Sawyer Abroad

Title: The Trumpet of the Swan

Title: The Trumpet of the Swan

Educational Properties: Easy tie-in to a music appreciation lesson if you have similar taste as White, who supplies a mixture of American standards (‘Summertime,’ ‘There’s a Small Hotel’ and ‘Beautiful Dreamer’ among those featured) and classical pieces (Brahms’ ‘Cradle Song’ mentioned by name, also Bach, Beethoven and Mozart) for Louis’s set list. A playlist drawn from and inspired by the book could very easily be created. The Trumpet of the Swan was also adapted for symphony in 2011 by Marsha Norman and received very positive reviews – if I ever expand into adaptations, that is certainly one I would like to try.

Educational Properties: Easy tie-in to a music appreciation lesson if you have similar taste as White, who supplies a mixture of American standards (‘Summertime,’ ‘There’s a Small Hotel’ and ‘Beautiful Dreamer’ among those featured) and classical pieces (Brahms’ ‘Cradle Song’ mentioned by name, also Bach, Beethoven and Mozart) for Louis’s set list. A playlist drawn from and inspired by the book could very easily be created. The Trumpet of the Swan was also adapted for symphony in 2011 by Marsha Norman and received very positive reviews – if I ever expand into adaptations, that is certainly one I would like to try.