The cover makes this look fairly campy, but the actual story hearkens to North Sea folktales. Sign me up.

Title: A Stranger Came Ashore

Title: A Stranger Came Ashore

Author: Mollie Hunter (1922-2012)

Original Publication Date: 1975

Edition: HarperTrophy (1995), 163 pages

Genre: Fantasy. Suspense.

Ages: 9-14

First Line: It was a while ago, in the days when they used to tell stories about creatures called the Selkie Folk.

It is a dark and stormy night on the Shetlands Islands when the Norwegian ship Bergen wrecks and a solitary man washes ashore in the isolated community of Black Ness. Calling himself Finn Learson, the good-looking young man secures shelter in the Henderson household, charming the family and their neighbours and quietly making himself indispensable while paying court to his hosts’ lovely daughter Elspeth. Only twelve year old Robbie Henderson finds it hard to trust the stranger. As omens appear in the funeral fire and Elspeth grows listless, Robbie begins to see something menacing behind Finn’s ready smile. Concerned for his sister, Robbie sets out to discover the truth about the stranger – and when he does, he will need to find help, or Elspeth will suffer a terrible fate…

The first thing to understand about A Stranger Came Ashore is that it is deliberately written in the style of an oral folktale. Mollie Hunter was Scottish and she tried to recreate the feel of Shetland customs and concerns; as such, there is a distinct cadence to the writing, a pattern of speech rather than straight narrative. It makes the novel feel distinctly personal, as a tale told directly to you, yet it’s also distancing – this is a tale of a while ago and Hunter does not play up the drama. Even knowing what to expect, the effect is momentarily very strange and perhaps even a deal-breaker for those expecting the techniques of modern storytelling. However, once you grow accustomed to the style, it becomes both lilting and propulsive, such that I have more trouble deciding where to end my quotes than where to start.

So Robbie swithered and swayed in the opinion that was never asked, and meanwhile, Finn Learson was getting acquainted with all the rest of the people in Black Ness. Very easy he found this, too, for all that he was a man of few words, since there is nothing Shetlanders enjoy better than visiting back and forward in one another’s houses.

Sooner or later also, on such occasions, out will come the fiddle. All the young folk–and very often some of those that are not so young–will get up to have a dance; and the first evening that this was the way of things in the Hendersons’ house, Finn Learson showed the lightest, neatest foot in the whole company.

He was merry as a grig, too, clapping his hands in time to the fiddling, white teeth flashing all the time in a laugh, eyes glittering like two great dark fires in his handsome head. No amount of leaping and whirling seemed to tire him, either; and curiously looking on at this with Robbie and Janet, Old Da remarked,

“Well, there’s one stranger that knows how to make himself at home on the islands!”

Hunter laces this book with details of Shetland culture, including their holiday traditions, superstitions, social conventions, the tug of war between pagan and Christian customs, the threat of the press gang, and all the way down to floor plans and furniture: Old-fashioned beds for the islanders were made like a large box complete with a lid on top and a sliding door on one side. There were air-holes in the sliding doors, neatly pierced in the shapes of hearts and diamonds; the box beds themselves stood on legs that raised them above drafts… This gives A Stranger Came Ashore plenty of crossover appeal between kids who like the particular atmosphere of British fantasy and kids who enjoy historical fiction. In other words, I would have loved it growing up if I’d only known it existed.

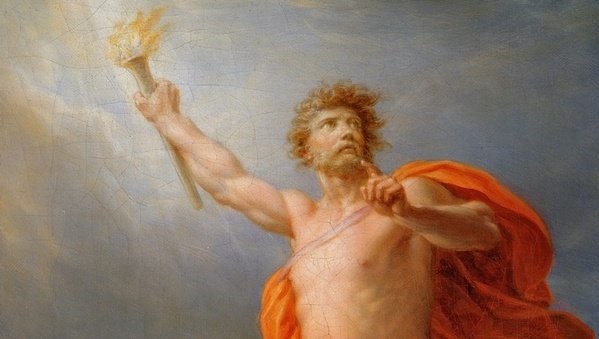

The fantasy elements of A Stranger came Ashore are built on ancient motifs. The Great Selkie is drawn ashore by the gold of a young girl’s hair – he has the power to charm the girl and her family, but is bound to speak only truth. This makes Finn Learson a trickster who nevertheless offers recompense to the families he hurts as he willingly takes on the work of the village, and further insists that the Hendersons accept an ancient gold coin, “for it may still cost you more than you think to have me here.” His sea-magic is powerful, but opposed by other elements and Robbie’s role in the story is to be the messenger and summon those other elements. It’s fairly mythic for such a quick read.

Unfortunately, Robbie does have a tendency to be outclassed and upstaged from his own story, as does Elspeth, the damsel in distress who never even realises she’s in danger. Finn Learson, with his charming facade and careful words, owns the book – at least until the final third when Yarl Corbie shows up.

Yarl is both the best and worst thing about A Stranger Came Ashore. He’s a bitter wizard who lost his love to the Great Selkie years ago, and now grinds along as the village schoolteacher, terrifying his pupils and inspiring wild rumours of ancient magic. It’s easy to understand why Robbie is so reluctant to approach such an intimidating and possibly crazy man – and this also forms a smart contrast with the smiling, seductive Finn, for Yarl Corbie acts like a villain but in truth plays the hero. From his first appearance this book is his:

To begin with, he had the nickname of Yarl Corbie, for that is the nickname the raven has in Shetland, and he looked like nothing so much as a huge raven.

His nose was big and beaky. His skin was swarthy. His eyes glittered in a sharp and knowing way. He was tall, but very thin and stooped, and he dressed always in black. Besides which, he always wore a tattered, black, schoolmaster’s gown that flapped from his shoulders like a raven’s wings. And like the raven, he was solitary in his habits.

There was yet another reason, however, for his nickname of Yarl Corbie. Long ago, it was said, in the days when this schoolmaster was still only an unchristened child, he had been fed on broth made from the bodies of two ravens. This, it was also said, had gifted him with all the powers of a wizard; and it was this, of course, which had given Robbie his idea.

Yet here was the snag of it all. Robbie was deadly afraid of Yarl Corbie; for Robbie, it has to be remembered, was twelve years old at that time, which was certainly not old enough for him to have lost his fear of wizards. It has to be remembered too, that Robbie was Shetland born and bred; which meant that deep, deep down in his blood and in his bones there lived the Shetlander’s ancient fear of the raven and its croaking cry of death.

The fact that this quote was pulled from page 98, over halfway into the novel, gives rise to the only significant problem I have with A Stranger Came Ashore. There is no earlier appearance by the schoolmaster, no brief cameo or reference to offer any hint that this man could hold a solution to Robbie’s problem. The lack of foreshadowing guarantees that his fortuitous knowledge of the Great Selkie feels like a deus ex machina rather than an organic part of the worldbuilding. He’s so cool that I didn’t really mind, but it’s a significant dramatic flaw that could have been cleared up with just one line, and I wish an editor had intervened on this point.

This is the only notable failing of the book and it’s not one likely to bother its intended young audience. Children who’ve enjoyed hearing folktales read to them will find here a longer fiction with the same feel, and Mollie Hunter’s style lends itself very well to reading aloud besides. There is menace and suspense, but it has none of the love for grotesquerie found in something like Coraline and is leisurely paced and intelligently written, like much of 70s middle grade. A fine addition to your family’s fantasy collection, especially if you prize a northern setting.

See Also: Seven Tears Into the Sea for a defanged teen romance take on selkies. The Stones are Hatching for a nihilistic deconstruction of British folklore and boy heroes.

Parental Guide and spoilers for the ending.

Violence: Very mild. There are some eerie omens and a vision of Elspeth dressed for some deathly bridal. It is revealed that girls who go to the Great Selkie’s underwater palace eventually grow homesick and drown when they attempt to return to the land, which makes for some unsettling imagery.

One seaside brawl. Yarl Corbie has a knife he likes to wave around and he easily scares Robbie into keeping silent about his wizardry. In the end Yarl becomes a raven and blinds Finn in one eye, sending the Selkie back to the sea.

Values: Lots of Shetland folk traditions are included here, and given that it’s rather hard to find children’s books set on the Shetland Islands, that’s enough for a recommendation already. Although it’s not a retelling, it is a folktale by nature and so is pro family and tradition.

Role Models: Robbie is a good, imaginative boy but also timid and superstitious, and so the only way he can save his sister is to conquer his fears one by one – of the dark, the schoolmaster and the stranger. He rises to the challenge yet also feels compassion for his family’s defeated enemy at the last when he believes Yarl Corbie fully blinded the Great Selkie.

“But a selkie hunts with its eyes,” he exclaimed. “And so you might as well say you’ve doomed him to starve to death!”

“Would that be so bad?” Yarl Corbie asked.

“I don’t know,” Robbie admitted. “But it’s cruel, all the same.”

Yarl Corbie shrugged. “The thought does you credit, I suppose,” he said drily.

Educational Properties: It would springboard nicely into a research session on the Islands, whose history and culture is not well known, as well as selkie folklore.

End of Guide.

It will probably be a while before I come across any more of Hunter’s books – although a prolific writer, relatively few of hers have migrated to America and many appear out of print. However, she’s definitely on my list to watch out for.

Title: Stormy, Misty’s Foal (Misty #3)

Title: Stormy, Misty’s Foal (Misty #3)

Title: The Midnight Fox

Title: The Midnight Fox

Title: Sea Star: Orphan of Chincoteague

Title: Sea Star: Orphan of Chincoteague

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Title: Flower Fairies of the Spring

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families.

Out of curiosity I made a list of the poems to see how often the rhyme schemes and templates repeated, to find that there were no exact replicas. When Barker reused a rhyme scheme she would change the number of stanzas, ensuring that every rhyme had its own face. I expect some repetitiveness would start to appear in the seven companion volumes but for now everything is very fresh, and in truth I would be very surprised if the artistic quality of subsequent installments ever dropped. Highly recommended to all English and Anglophile families.

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

Title: Stuart Little

Title: Stuart Little