Remember when you could buy a pony for 100 dollars? Me neither.

Title: Misty of Chincoteague (Misty #1)

Author: Marguerite Henry (1902-1997)

Illustrator: Wesley Dennis (1903-1966)

Original Publication Date: 1947

Edition: Aladdin Paperbacks (1991), 174 pages

Genre: Animal Stories. Adventure.

Ages: 5-11

First Line: A wild, ringing neigh shrilled up from the hold of the Spanish galleon.

Paul and Maureen Beebe are growing up on their grandparent’s horse farm in the isolated commuity of Chincoteague Island. Tired of bonding with colts that always get sold, the siblings set out to earn 100 dollars to spend at the annual Pony Penning Day, when the wild herds on Assateague Island are rounded up and the colts auctioned. Paul and Maureen have their hearts set on an elusive mare called the Phantom, who has avoided capture two years in a row. Faced with the challenges of earning enough money, capturing and gentling her, an added complication is thrown into the mix when Pony Penning Day arrives and reveals that this year the Phantom has a colt of her own…

The Newbery list is certainly hit-and-miss but (with a few notable exceptions like The Phantom Tollbooth and Little House on the Prairie) they have historically been quite good at recognising children’s classics when they appear on the American stage and that’s exactly what the 1948 Honor Book Misty of Chincoteague is. A horse story that can appeal to a broad age range, full of action and purpose as the protagonists dedicate themselves to a series of goals, yet devoid of the emotional punches that are found in other famous horse books like Black Beauty. The ending is memorable and wistful, but without tragedy, and the story as a whole is sunny, lacking any villains beyond circumstances that must be overcome. With Paul and Maureen sharing viewpoints, it even has equal appeal to boys as well as girls, something that has become unusual in the genre.

Marguerite Henry instills her book with a strong sense of place right from the start, not only with the wild herds on Assateague but also the fishing community of Chincoteague, whose independence forms a parallel to the ponies, for these men and women are also making do with less, cut off from the larger nation yet thriving. There’s a real American ethos within the book and it captures a place in time with its own culture and cuisine (there’s a small pile of food descriptions with oysters, cornbread, clam fritters, dumplings and wild blackberry jam). Henry spent a great deal of time on Chincoteague, and even though she changed the larger “true story” drastically, I have no reason to distrust her eye for detail, which even renders the old-timers’ accent through Grandpa and Grandma Beebe:

Maureen: “…if you came here to Pony Ranch to buy a colt, would you choose one that was gentled or would you choose a wild one?”

Grandpa chuckled. “Can’t you jes’ see yer Grandma crow-hoppin’ along on a wild colt!”

“Thar’s yer answer,” laughed Grandma, as she cut golden squares of cornbread. “I’d take the mannerly colt.”

The real draw are the horses, of course, and Henry supplies two perfect equine characters in the Phantom and Misty. The Phantom has a map of the United States on her withers – a clear cut case of symbolism in a patriotic novel. “Lad,” [Grandpa] said, “the Phantom don’t wear that white map on her withers for nothing. It stands for Liberty, and ain’t no human being going to take her liberty away from her. … The Phantom ain’t a hoss. She ain’t even a lady. She’s just a piece of wind and sky.”

The only thing that really tames the Phantom is her “colt” (islanders in this book refer to every young horse as a colt, which I thought only referred to males), whom Paul names Misty. Misty drives none of the plot – she is the counterweight to the Phantom’s wildness, playful and domestic by nature, belonging to Chincoteague from the moment her hooves land on the shore. Slowly and dejectedly the wild ponies paraded through the main streets of Chincoteague. Only the Phantom’s colt seemed happy with her lot.

I would be remiss not to single out Wesley Dennis as a large part of Misty of Chncoteague‘s charm, as he always supplies the perfect image for every scene. The personalities of every character, horse and human, shine through and equal the best of Garth Williams’ work. Dennis draws comic characters without caricaturing and his equines emote without crossing the line and losing their realism. His dramatic talents also enhance the impact of what is a fairly short and low-stakes adventure tale, making the risks feel bigger and the triumphs sweeter. Nicely done.

I have no complaints to make. Misty of Chincoteague was quite nearly as enjoyable today as it was when I was a child. It makes a lovely addition to the family bookshelf and would make a good read-aloud for high summer, maybe even for 4th of July week given how civic minded the story is. For more on the 1940s value system this is steeped in, check out the Parental Guide below.

Violence: The book opens with a Spanish shipwreck in which the original Assateague ponies, destined for the mines of Peru, successfully swim to shore. All hands perish in the storm, with Henry softening that blow by depicting the Captain as gold-hungry and indifferent to the ponies’ welfare. In the present day, there’s a high ratio of distressed ponies, due to their captivity on Pony Penning Day and the auction. None are injured or die.

Values: Hard work and responsibility as Paul and Maureen seize any type of summer employment they can find to earn money for the Phantom – and then do it all over again to pay for Misty. They have a whole series of chores round the Ranch and almost every time the grandparents are depicted they are in the middle of work, whether that be feeding chickens, preparing food, maintaining the horses or doing laundry.

Misty is very patriotic in tone – Pony Penning revenue goes toward maintaining the island’s fire department, school is “what me and Grandma pays taxes for,” every roundup man is well-known by his day job and the island is a well oiled machine with every man, woman and child doing their part to keep it running. The kids have a great deal of independence and are allowed their own goals and their own time to tell about them, but once Paul is picked for the roundup crew he is expected to obey his leader’s orders (and is promptly rewarded when following instructions leads him to the Phantom). There’s even material about fair play, as Paul and Maureen pull a wishbone to decide who gets to race the Phantom, and liberty, when Paul makes a hard decision about the Phantom’s future.

Role Models: Paul has a keen head for business but also a romantic streak, and he’s the one most attuned to the Phantom. Maureen is given less to do, which disappointed me growing up, and a friend of mine found several disparaging remarks (such as “Quit acting like a girl, Maureen!”) concerning as a parent. As such, I paid close attention to the topic and found the only source of the quotes to be Paul, which could easily be attributed to big brother posturing. Such occasional put-downs never stop him from treating her as an equal partner in their plan to buy and gentle the Phantom and the actual text never devalues Maureen’s (or Grandma Beebe’s) contributions. It’s certainly true that she doesn’t get any action scenes, but it’s also true that not everything has to be about girls. There are thousands of horse and pony books catering to the pre-teen girl demographic, books which I devoured indiscriminately and which rarely ever give equal time or weight to male characters – such that when I first read Misty I assumed that Maureen should naturally have a greater bond with the Phantom just because she was a girl. No one ever labels that a cause for concern, so a mix of recent and vintage horse books would balance out nicely.

Aside from that, not a lot to say. Every character is trustworthy and fair and probably most kids would wish they had grandparents like the Beebes. Oddly, Paul and Maureen’s parents are absent due to being in China (I guess Henry thought orphaning them would be too predictable).

Educational Properties: I would normally advise researching the true story behind the fiction, but in this case there is no historical sweep that would prove schoolworthy and Misty is meant for such young readers that there’s no point digging for disillusion here.

On the other hand, the wild ponies have been observed for decades, which offers quite a lot of information and data for a bit of natural science. Theories on how the ponies arrived on Assateague are also well worth researching. Those in nearby states might want to take a trip to the islands as well.

End of Guide.

I have copies of all three sequels to Misty, which I will be posting in the next few months. I can then embark on her larger bibliography, which consists mostly of other horse stories (one of which won the Newbery Medal), many of which were also illustrated by Wesley Dennis.

Up Next: A springtime poetry collection by Cicely Mary Barker.

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

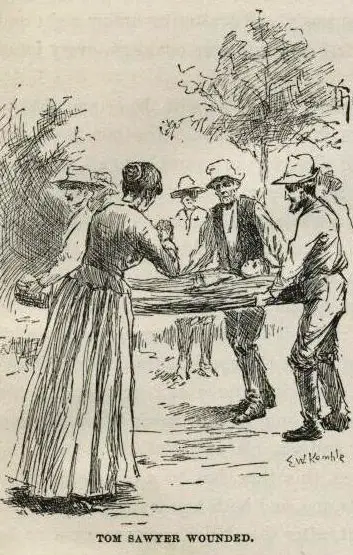

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

Title: Tom Sawyer, Detective

Title: Anne of Windy Poplars (Anne Novels #4)

Title: Anne of Windy Poplars (Anne Novels #4)

![Image result for cold comfort farm book penguin]](https://www.penguin.co.uk/content/dam/prh/books/604/60407/9780241418895.jpg)

Title: The Stones are Hatching

Title: The Stones are Hatching

Title: The Trumpet of the Swan

Title: The Trumpet of the Swan

Educational Properties: Easy tie-in to a music appreciation lesson if you have similar taste as White, who supplies a mixture of American standards (‘Summertime,’ ‘There’s a Small Hotel’ and ‘Beautiful Dreamer’ among those featured) and classical pieces (Brahms’ ‘Cradle Song’ mentioned by name, also Bach, Beethoven and Mozart) for Louis’s set list. A playlist drawn from and inspired by the book could very easily be created. The Trumpet of the Swan was also adapted for symphony in 2011 by Marsha Norman and received very positive reviews – if I ever expand into adaptations, that is certainly one I would like to try.

Educational Properties: Easy tie-in to a music appreciation lesson if you have similar taste as White, who supplies a mixture of American standards (‘Summertime,’ ‘There’s a Small Hotel’ and ‘Beautiful Dreamer’ among those featured) and classical pieces (Brahms’ ‘Cradle Song’ mentioned by name, also Bach, Beethoven and Mozart) for Louis’s set list. A playlist drawn from and inspired by the book could very easily be created. The Trumpet of the Swan was also adapted for symphony in 2011 by Marsha Norman and received very positive reviews – if I ever expand into adaptations, that is certainly one I would like to try. itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

itle: Around the World in Eighty Days (Extraordinary Voyages #11)

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated.

Given that I can only review 52 books per year and since the Extraordinary Voyages all function as stand-alones, this is one series I will have to proceed with at my own slow pace. In case you’re wondering why I have not mentioned or pictured a hot air balloon in this review, that’s because the balloon was a later Hollywood addition (ignoring the obvious fact that a balloon is by no means a reliable way to get from point A to point B instead of drifting to point J). Verne’s first contribution to the Voyages was actually Five Weeks in a Balloon, which is where the association of Verne and balloons began. Adding to the confusion, Around the World in Eighty Days is sometimes published in omnibus form with Five Weeks in a Balloon, though the stories are entirely unrelated. Title: Anne of the Island (Anne Novels #3)

Title: Anne of the Island (Anne Novels #3)

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Title: Seven Tears Into the Sea

Wild Western Thimbleberry

Wild Western Thimbleberry