All authors of historical fiction should make proper scholarly use of the Author’s Note – no matter what age group they’re writing for. Aside from that, this is an entertaining novel that only took me a day and a half to read.

Title: Black Duck

Title: Black Duck

Author: Janet Taylor Lisle (1947-)

Original Publication Date: 2006

Edition: Philomel Books/Sleuth (2006), 252 pages

Genre: Historical Fiction. Mystery.

Ages: 10-12

First Sentence: Newport Daily Journal, December 30, 1929: COAST GUARDS KILL THREE SUSPECTED RUM RUNNERS.

It’s 1929, Rhode Island, and rum running is in full swing, with every local family forced to pick a side – easy money on the wrong side of the law, or ratting out the neighbours to what could be the crooked side of the law. Teenagers Ruben and Jeddy are best friends but Jeddy’s father is the local police chief while Ruben’s father is slowly getting ensnared in the bootlegging industry, despite his efforts to remain neutral. One day, Ruben and Jeddy find a dead man in an evening suit washed up on the beach, but by the time they’ve returned with a cop the body’s vanished. Ruben made the mistake of searching the body and soon finds himself plunged into the dangerous underworld of the rum runners, who think he’s taken something valuable from the corpse. Isolated from Jeddy as well as his own father, Ruben gains a new ally in the dashing captain of the Black Duck, the most elusive of the smugglers, but one whose tiny local outfit is threatened by the encroaching big-city operations. Ruben, in way over his head in a world of warring criminal factions and shifting loyalties, becomes the only witness to a terrible night on the water…

This middle-grade novel by Janet Taylor Lisle (who won a Newbery Honor in 1990 for Afternoon of the Elves) is based on the true story of the Black Duck, the fastest rum running vessel on the Rhode Island coast, which was caught by the Coast Guard on the 29th of December in a dense fog. The Coast Guard opened fire on the cabin and three of the four man crew died, while the captain lost a thumb and later insisted that no warning had been given before the authorities opened fire. Given they were ambushed in a fog right after a pick-up of liquor, it seems fairly likely that someone tipped off the authorities to the Black Duck’s whereabouts, but in the end nothing was ever proven and, despite local outrage, the Coast Guard was cleared of all wrongdoing in the incident. Lisle changed this story in a few significant ways, and there will be more information on that in the Parental Guide.

Obviously there is plenty here to hang a novel on, and Lisle makes use of an interview framing device to help propel the plot and its mystery, as a teenager interviews elderly Ruben about the events in his youth, interspersed with (fictional) newspaper clippings about the Black Duck, raising new questions as Ruben answers the old. Lisle knows how to use a hook of the old-fashioned kind when she ends her chapters: There were probably ten perfectly legal reasons why Police Chief Ralph McKenzie would be up late counting out stacks of money at his supper table. I just couldn’t right then think of what they might be. The plot thickens constantly and involves multiple factions beyond a simple cops vs. criminals outlook, with small local outfits, big time operators muscling in, crooked cops on the take, and civilians trying and often failing to stay clear of the whole mess. It’s a rich soup of conflicts, secrets and betrayals. The rum running world is shown in perfectly comprehensible detail – anything that won’t fit organically into Ruben’s story gets brought up in the interview sections – with the governing laws and nighttime operations easy to understand.

I’d never been on the beach at Brown’s, though I’d passed it going upriver on the Fall River boat a couple of times. It was a natural cove sheltered by a dip in the coast, a good place for a hidden landing. When I rode up, about twenty men were already there and a bunch of skiffs were pulled up on the beach, oars set and ready. The place was lit up bright as day with oil lanterns planted on the beach and car headlights shining across the sand. When I looked across the water, I was astonished to see a freighter looming like a gigantic cliff just outside the blaze of lights. It was in the process of dropping anchor. I soon found out that she was the Lucy M., a Canadian vessel that usually moored outside the twelve-mile U.S. territorial limit of the coast to avoid arrest.

The way the Prohibition law was written, the Coast Guard couldn’t touch an outside rig, since it was in international waters. So ships from Canada and the West Indies, Europe and Great Britain would lie off there, sell their liquor cargos and unload them onto rum-running speedboats like the Black Duck to carry into shore. Sometimes as many as ten or fifteen ocean-going vessels would be moored at sea, waiting to make contact with the right runner. “Rum row,” these groups of ships were called. You couldn’t see them from land, but you knew they were out there lying in wait over the horizon. It gave you an eerie feeling, as if some pirate ship from the last century was ghosting around our coast.

I couldn’t believe the Lucy M.‘s captain would be so bold as to bring her into Brown’s, where any Coast Guard cutter in the area could breeze up and put the pinch on her. Nobody at Brown’s seemed worried about it, though, and unloading operations soon commenced.

Lisle’s writing is very straightforward and plain, lacking the richer textures and colours of great historical fiction, but she’s good at telling an exciting story and she doesn’t pack Black Duck out with a load of extra gritty details – no foul language, graphic violence or nasty medical conditions – to artificially propel her middle grade story into the reach of the larger young adult market.

One drawback to the novel is a lack of emotional weight. By rights, the story should be perfect for it, with death and betrayal centered around the broken friendship of two boys. However, Jeddy retreats into the background halfway through the book and is barely glimpsed after that, mitigating the impact of subsequent events. It’s a pity, as their relationship is well-drawn, with a tense mixture of small lies and family loyalties pulling them apart. Once that happens, though, Ruben is left fairly isolated save for his visits to the local hermit, Tom, and his interactions with Jeddy’s older sister Marina, whom Ruben is besotted with.

Marina is referred to on the dust jacket as “strong willed,” but I found it refreshing that Lisle did not make use of her as a cynical back door invite to girl readers – you know, “look, there’s a girl helping the boy protagonist and she’s just as important to the story, so please buy this book because boys don’t read enough anymore…” Marina’s role in Black Duck is closer to that of the good girls in old noir films than to a modern “strong female character.” In other words, Marina is not dressing as a boy and moonlighting with the Black Duck crew.

Ruben’s own character development proceeds along the classic path – he starts the story naive, seeking excitement and resenting the steady job he has waiting in his future, feeling unappreciated by his father and jumping at the offer of twenty bucks no matter the source. However, following the fate of the Black Duck’s daredevil crew, well…

A sadder and a wiser man

He rose the morrow morn.

My final thoughts on Black Duck could best be summed up by calling it decent. This sounds like a terribly low bar, but it’s an important one in these days of constant envelope-pushing. Lisle’s book is entirely suitable light reading, mixing an intriguing time period with a mystery format. It’s perfect for kids who enjoy the historical genre. However, it lacks staying power, and I would strongly recommend making it a buddy read with Farley Mowat’s The Black Joke, which looks at the rum running business from the Canadian side of things. Together the two books would offer a neat crash course in the coastal landscape of Prohibition for homeschooling families, and with that I offer a new category in my reviews:

See Also: The Black Joke by Farley Mowat, set in the early 30s off the coast of Newfoundland, considerably better written yet also far more boat-centric.

Onwards to the Parental Guide, packed with spoilers and historical links today.

Violence: The original corpse in the water is thusly described: Above it, swathed in a shawl of brown seaweed, a rubbery-looking shoulder peeked out, white as a girl’s. Above that, a bloated face the color of slate; two sightless eyes, open. And there in his neck, what was that? I saw a small dark-rimmed hole. … I went forward and felt around, trying not to brush up against the corpse’s skin. It had a cold, blubbery feel that turned my stomach. The murderers come back later, toting machine guns and killing Tom’s old dog because they tripped over her. The boys, hiding further down the beach and thinking that Tom’s been killed, come upon the scene after the gangsters leave.

Ruben gets kidnapped by the villains later, and then re-abducted by a bigger New York crew, who toss him into the back of the getaway car so roughly that he strikes his head on something and spends a considerable amount of time bleeding all over the place. After being rescued, he becomes the fictional fifth member of the Black Duck, who shelters in the tarp-covered lifeboat while listening to the gunfire above.

Lastly, Marina is a pretty girl. Ruben’s crush is obvious but never vulgarly described. A crooked cop takes an interest in Marina, and gives her a ride in his car under false pretenses. When he pulls over, she exits the vehicle immediately and flags down another driver to get home. Marina keeps this a secret, with the takeaway being she doesn’t think anyone would believe her side of the story. This whole sequence feels somewhat shoehorned into the plot, but it’s nowhere near as disturbing as Julie of the Wolves.

Values: Lip service is paid to good cops, but every single one in this story is crooked in some way or other, including Jeddy and his dad.

There’s some family dysfunction on display, though it’s fairly mild for modern youth literature and Ruben actually gets over his resentment of his straight-laced father. In fact, there’s a parallel between Ruben and his young present-day interviewer David, as they both chafe against working in the family business. Ruben came to accept it, and it’s shown how the friendship that develops over the interviews appears to have a good influence on young David.

The Black Duck crew is heavily romanticized and fictionalized, becoming an outlaw crew with Robin Hood allure: They were local men from local families with a need to make ends meet during hard times, different altogether from the big-city syndicates that were beginning to bully their way into the business at that time. Many folks quietly cheered them on around their supper tables, proud that one of their own could outsmart both the government and the gangsters. Their status as good guys makes their fate more impactful, but it’s also a questionable interpretation of events. More on that under Ed. Properties.

Role Models: This whole novel is about murky ethical dilemmas that the young teens at the heart of the story aren’t sure how to navigate. This is apparently a recurring theme in Lisle’s fiction. In consequence, Ruben, Jeddy and Marina flail around and never really come up with any answers to their questions. Jeddy clings with absolute loyalty to his father, ignoring all evidence against him. Marina falls in love with the Black Duck’s captain and says “if you have to make a choice, you do what’s best for the people you love,” but finds out that isn’t really an applicable rule when those “people you love” are in conflict. Ruben decides to move on with a civilian life while trying to forgive everyone involved in the Black Duck incident. Ruben’s got some old-school pluck, but his naievety and trusting nature get pretty frustrating after a while, coming across as willful blindness (like Jeddy’s) that he really can’t afford. It’s actually quite realistic.

Educational Properties: Okay, Lisle changed all the names of the crew of the Black Duck. Her captain is a fellow named Billy Brady, a daring and enterprising young man with a grassroots operation. It’s no wonder Marina’s in love with him. The real Black Duck was owned by a guy called Charlie Travers. Interesting switch takes place here – Charlie was the sole survivor of the shooting, whereas Lisle’s Billy is killed and a minor character survives instead, doubtless to increase the emotional factor.

Charlie Travers does appear to have started out as a hotshot kid, reworking the Black Duck’s engine to get up to 32 knots and proving nearly impossible to catch. However, he was a shady figure, becoming the partner of Max Fox, one of Charles ‘King’ Solomon’s lieutenants. Solomon was Boston’s answer to Lucky Luciano, being heavily involved in narcotics and bootlegging, gambling, prostitution and witness intimidation. When he died, Max Fox was one of the men who acquired his divvied-up territory. So if this Charlie Travers person was independent and local, he didn’t stay that way for long. Since Lisle changed all the names (except of the boat itself), this might not seem like important information, but I do feel that Lisle should have clarified her changes in the Author’s Note at the end, Ann Rinaldi style, given that this novel is inspired by real accounts. When Lisle has Marina say of the Black Duck’s crew “they kept clear of the syndicates and they didn’t carry guns,” she’s referring to the fictional Billy Brady, but what reader would know that without looking up the original newspaper clippings?

Therefore, in addition to Black Duck‘s excellent use in a study on Prohibition, I think it could also work as a demonstration of how stories can be retold and repackaged with opposing facts – historical references to machine guns and “King Solomon” become fictional references to unarmed men avoiding the syndicates. It’s kind of like Island of the Blue Dolphins (and oh, suddenly I can’t wait to unpack that “true story”).

End of Guide.

Lisle has a fair number of books out and I would be quite content to try a few more as I see them. I was surprised to find that Black Duck is her most popular work on GoodReads, but like I said, it’s both entertaining and decent, and post-millennium, decency is the first hurdle that any youth literature has to clear, at least on the Western Corner of the Castle…

Up Next: Teenage paranormal romance. Set on the west coast. Published in 2005. No, it’s not Twilight.

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Title: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

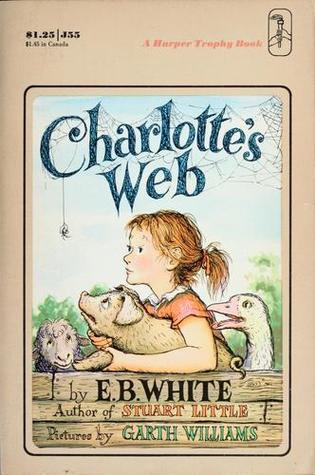

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Charlotte’s Web

Title: Shane

Title: Shane

Title: Time Cat

Title: Time Cat

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

Title: Anne of Avonlea (Anne Novels #2)

Title: The Hundred Dresses

Title: The Hundred Dresses

Title: Stuart Little

Title: Stuart Little

Title: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Title: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Title: The Court of the Stone Children

Title: The Court of the Stone Children