A comic parable for kids who will likely grow up to read Terry Pratchett.

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Title: The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man

Author: Lloyd Alexander

Original Publication Date: 1973

Edition: Dell Yearling (1992), 107 pages

Genre: Fantasy. Humour.

Ages: 9-12

First Line: “Please, master,” said the cat, “will you change me into a man?”

Lionel is an improbably nice cat whose master, the cynical wizard Magister Stephanus, gives him the gift of human speech. However, with this new trait Lionel begins to wonder what life is like as a man, and so Magister Stephanus reluctantly changes him into one – sending him to the nearby town of Brightford in hopes of curing the cat’s folly. Lionel’s journey is full of dangers and he encounters thieves, knaves and corruption in Brightford, but also generosity, courage and love. In the end Lionel must make a choice: does he wish to become an innocent feline once more, or remain human?

In the ten years after publishing Time Cat, Lloyd Alexander became one of the premier children’s novelists of his era, winning a Newbery Honor, Newbery Medal and the National Book Award for three separate works. The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man finds him post magnum opus and probably looking to decompress – hence another cat-centric fantasy, this time set in a generic medieval time that probably required only five minutes of world-building. The characters sport Dickensian names like Pursewig, Tudbelly and Swaggart and to all appearances it’s a fairly simple little book, a comic trifle. However, it is an obviously more sophisticated affair than Time Cat, and shows a new mastery and conviction of the form.

I mentioned in my review of Time Cat that its prose was not quite polished enough to made a great readaloud, a criticism which is no longer the case. Alexander’s writing is sharper, wry and intelligent enough to place real demands on a young reader’s vocabulary and cultural understanding – helped in large part by the character of the endearing snake-oil salesman Dr. Tudbelly, whose commercial patter features a sizable amount of Latin, cod-Latin and medical misuse. Read widely or miss the jokes:

“Everything is more confusing on an empty stomach. Natura abhoret vacuo. I dislike having my breakfast interrupted. It produces palpitations of the jejunum.”

Opening a compartment of the Armamentarium, Dr. Tudbelly took out the leftovers he had salvaged from the inn: the remains of chicken and some bread crusts.

“Here,” he said cheerfully, offering half to Lionel. “You’d better have something. You look a little green around the gills.”

“Gills?” cried Lionel, clapping his hands to his neck. “Am I turning into a fish?”

“Only a manner of speaking,” Dr. Tudbelly said. “Eat, my boy. It’s the best way to ward off splenetic chilblains.”

Combining memorable characters with wide-ranging comedy and clever writing makes The Cat Who Wished to Be a Man an easy book to recommend. Lionel’s absolute innocence as he careens from one problem to the next like Candide for 10 year olds creates ample plot, both humourous and suspenseful, all in a novel that barely breaks 100 pages. Throughout the silly escapade Lionel finds that as he grows more human he begins to lose his catlike qualities such as the ability to land on his feet, threading a theme of lost innocence into the mix. Indeed, it is implied that Magister Stephanus is himself to blame for Lionel’s “fall,” for:

“Since when does a cat not feel like a cat?”

“Since you gave me human speech.”

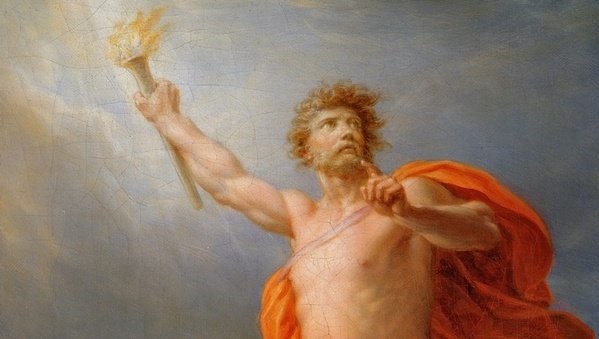

In some ways, Stephanus actually has more in common with science fiction doctors – tampering with the natural order of things like Moreau and Frankenstein – rather than the good wizard archetype who appears to restore order. There is also an odd variation on the Prometheus story, where the wizard regrets his interference in mankind’s evolution:

“When I first came here, the people of Brightford were tilling their soil with pointed sticks. I pitied them in those days. So I gave them a gift: all the secrets of metalworking. I taught them to forge iron for plows, rakes, and hoes.”

“They must have been glad for such tools.”

“Tools? They made swords and spears! There’s not one gift I gave them they didn’t turn inside out, upside down, and wrong side to. They were a feeble, sickly lot, so I taught them to use roots and herbs for medicines. They found a way to brew deadly poisons. I taught them to make mild wine; they distilled strong brandy! I taught them to raise cows and horses as helpful friends; they turned them into drudges. Selfish creatures! They care for nothing, not even each other. Love? They love only gold.”

Once Lionel arrives in Brightford, he finds himself taking sides in a conflict between young innkeeper Mistress Gillian and corrupt Mayor Pursewig, who seeks to put her out of business and take control of the inn’s revenue himself. Lionel makes a much better man than he ever did a cat, being appalled at Pursewig’s greed rather than bored and indifferent. Really Lionel should have gone home immediately upon realising how hard it was to get a bowl of milk in human form, and slept on a shelf the rest of the day. Instead, Lionel learns the finer points of humanity as the situation in Brightford goes from bad to worse. After a good samaritan intervenes on his behalf, Lionel said glumly to him:

“You’d have been better off if you hadn’t tried to do us a good turn.”

“I suppose I would,” replied Tolliver, with a grin. “Even so, I’d do the same again.”

Lionel looked at him in surprise. “Why, not even a cat would make the same mistake twice.”

“Well, now,”said Tolliver, “what may be true for a cat isn’t always true for a man. I might regret doing a wrong thing, but I’ll surely never be sorry for doing a right thing.”

Alexander grew in subtlety after Time Cat, and the morals are seeded through the narrative naturally rather than given grand summations. The ending is extremely pat but it still avoids insulting the intelligence, and the comedy runs quite a gamut (without dipping into vulgarity), from slapstick to rhetorical confusion, and with the added bonus of a Kafka shoutout:

“Silence!” cried Pursewig, rapping on the table. “I’ll judge the facts for myself.”

“They’re already noted down,” said Swaggart. “And the verdict. Guilty as charged.”

“Guilty?” exclaimed Lionel. “Of what?”

“That will be determined in due course,” replied Pursewig. “One thing sure: You’re guilty of something. Otherwise, you’d not be on trial in the first place.”

This is a clever little book and it might give its young readership a taste for other clever books going forward – after all, it’s not so far from Alexander’s cats-eye view of humanity to Terry Pratchett’s musings from the nome perspective in Truckers. There’s more thoughtful material to be found here than in many modern fantasies of five times the length. Vintage wins again.

See Also: Time Cat, which is suitable to a slightly younger readership.

Parental Guide.

There’s a little romance between Lionel and Gillian. He learns what kissing is and, although they get off to a rocky start given that she thinks he’s a half-wit, they do end up in love. This subplot is integral to the book’s themes, so I can’t really fault it for being an improbable love story.

Violence: Lionel spends much time being threatened by crossbow, thumbscrew, drowning and a burning building – nothing is very detailed, though (what thumbscrews actually do isn’t described). Swaggart gets into some G rated harassment of Gillian, reminiscent of the old swashbuckler films. “Vixen! You’ll wish you’d sung me a sweeter tune!” Nobody dies or is seriously injured and the villains are quickly dispatched at the end, with Swaggart transformed into a skunk and Pursewig humiliated before the town and somehow demoted to dishwasher.

Values: Magister Stephanus condemns humanity as greedy, violent and self-serving at the start of the book, and Lionel is never able to prove him wrong. Instead, Lionel embraces the better nature of humanity and refuses the offer of returning to cat form. Indeed, the only way he could go back would be by forgetting everything that had happened, losing his memories to reclaim the unknowing Edenic state of the animals. Fairly theological for so small a tale.

Lionel accepts the world as it is, the good and the bad. Stephanus refuses to do the same (in the one plot thread that doesn’t end in a neat little bow) and remains a bitter and begrudging hermit, unconvinced to the end.

Role Models: Lionel is a brave, good-natured innocent, making for a nice hero who is comical yet both sympathetic and just. Gillian has inherited her father’s inn and has a good head for business, also holding her own against the “village gallants” by giving them a whack of her broom. The illustrious Dr. Tudbelly is quite generous with his time, ready to commit to Lionel’s cause or enact a little stone soup scamming for the benefit of Brightford. Even Stephanus, a powerful wizard, spends much of his day gardening and cooking rather than enchanting his house to run itself (as is stated to be well within his power).

Educational Properties: If you and your family are studying Latin, this might have some added use. Otherwise, just read, reference and discuss.

End of Guide.

At this point I am thoroughly charmed by Lloyd Alexander and look forward to my next acquisition of his, whatever it may be.

Up Next: A Newbery Honor Book by Marguerite Henry.

Title: Time Cat

Title: Time Cat